Dido Queen of Carthage

Dating Dido

Marlowe's works are all difficult to date precisely even within the author's relatively short working life, but Dido is perhaps the hardest of all.1 In Marlowe's lifetime there are no entries relating to the play's publication in the Stationers' Register nor any record of performances in Henslowe's Diary or elsewhere to help us. Neither are there any specific topical references within the play itself that might help date it directly, or even to position it in chronological order relative to any of Marlowe's other works.

The boundaries of possible composition are thus that of Marlowe's potential productive period, ranging from his time at Cambridge University (1580-87) to his demise at Deptford on 30 May 1593. The only printed edition of the play, the 1594 Quarto, post-dates this latter event. Even the possible contribution of Nashe does not greatly help with dating. He was at Cambridge from 1581 to probably around the middle of 1588, and is generally agreed to have lived in London thereafter. So any potential period of co-located collaboration is not much further restricted.

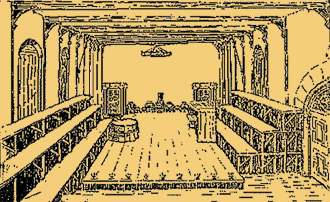

The recorded playing of Dido by "the Children of her Maiesties Chappell", aka the Children of the Chapel (Royal), on the title page of the 1594 Quarto raises more questions than it answers. The company of boys had played regularly at Court for nearly a century up until 1584, when payments are still recorded to the Master of the Chapel for plays performed at Christmas. It is also recorded that William Hunnis, as Master of the Children of Her Majesty's Chapel, took a joint sub-lease on the private (first) Blackfriars theatre in December 1581 where plays were performed by different boys' companies until 1584 when the theatre was forced to close.

There are only sporadic traces of the Children of the Chapel as an acting company thereafter. They did not play at court again until 1601. Performances by the company on the road are recorded at Norwich and Ipswich in 1587, Fordwich and Lydd in Kent as well as Poole in 1590, and Leicester in 1591,2 so they did not completely cease their dramatic activity (although speculation that they performed at Croydon in the summers of 1592 and 1593 are purely circumstantial). The extant records for the company thus appear to give no significant clue as to when the Children of the Chapel might have performed Dido,3 although proposes some possibilities4 as we will shortly come to.

So any tentative dating must rely solely on a subjective and comparative view of the style, quality and maturity of both the poetry and stagecraft in an attempt to posit a relative dating. An initial observation is often that the play is to some extent an exercise in translation, which may point to it having been written during Marlowe's time at Corpus Christi. It is then compared stylistically to Tamburlaine, which is generally assigned a date of 1587. This becomes a subjective exercise with predictably varying conclusions. Earlier critics saw a mature style, dating the play more towards the end of Marlowe's career. Others see enough fluency and craftsmanship to at least date the play after Marlowe's University days and Tamburlaine. In contrast, analysis of the internal evidence of others identifies a certain immaturity of style that suggests Dido was (initially at least) written before Tamburlaine, these latter commentators tentatively dating the main composition of Dido to around 1585-86 whilst both Marlowe and Nashe were at University. Considerations are also given as to whether, and if so to what extent, an original text was edited for publication in 1594.

Some of the points made historically for these various arguments can be summarised as follows:

- An early view on style by is that the use of couplets in parts of Dido suggest it was written at the same time as Hero and Leander; namely in 1593, with Marlowe leaving the play also unfinished at his death.5

- cites Dido's "dramatic looseness" along with "unfinished drafts" of some of Marlowe's most celebrated lines that subsequently appear in Tamburlaine and Doctor Faustus as indicators of a substantially "immature work". In addition "the classical story and close dependence on Vergil naturally point to the academic period", and he is of the view "that the tragedy was probably sketched in its earliest form before Marlowe left Cambridge" in 1587.6

- At the same time, Tucker Brooke is also of the opinion that "much of the blank verse shows very considerable finish and fluency" which he believes shows the extant play text dates "from a later period" than the pair's university days. In his opinion "Marlowe subjected his old Cambridge play to a complete revision at about the period when he was writing Edward II and the not disimilar Hero and Leander".7

- notes that Dido is comparable in type to the other plays performed by the Children of the Chapel Royal in the 1580's.8

- cites the poor stagecraft of Tamburlaine in concluding it is "inconceivable" that the more proficient Dido could have been written before Tamburlaine.9

- Disputing this point, claims that Tamburlaine is in fact "well adapted for performance on the bare stage of the public theatre", whilst Dido appears more appropriately designed for performance by child actors in a private theatre.10

- notes that some speeches are significantly different from the general immature style of set declamation, so whilst the play "undoubtedly dates from his Cambridge days", there is evidence of some revision late in Marlowe's career.11

In the first Revels edition of the play, editor disputes many of these earlier views, particularly those arguing for stylistic maturity compared to Tamburlaine. He notes that whilst "Marlowe is experimenting in Dido with all kinds of variation", "nevertheless the verses are nearly all end-stopped, there are very few feminine endings ... and the prevailing impression must be that Marlowe ... was mostly writing in single lines, whereas even in Tamburlaine he was sometimes writing in verse paragraphs".12. The playwright uses immature alliteration, and the frequency and style in which characters address each other directly by name, and themselves in the third person, would seem to predate Marlowe's more mature and natural conversational style in other plays.13. Oliver also opines that those examples of mature revision cited by Clemen rather arise immediately out of a direct translation from , Marlowe's source. He is firmly of the opinion that here is "a young dramatist making insufficient changes in passages derived directly from a narrative and epic poem", and that Marlowe can be seen to develop from this experience in the two parts of Tamburlaine.14 Thus Oliver opts for an early date of composition, before Tamburlaine.

challenges this pervading view that Dido is an early Marlowe work written "as a prentice piece in his student days" for academic performance at Cambridge. He views this as a "myth" that has been "repeated into acceptance" even though "at no point does actual evidence come into play".15 The extant play is far more than a University student exercise in translation. Whilst following his source narrative closely, "Marlowe also reshapes and extensively supplements his Virgilian material".16 And would Marlowe really have had time to write a play at Cambridge with an arduous 18 hour daily routine demanded of the conscientious student?

Any notion that the student Marlowe could have written the play for the London stage is dismissed by Wiggins, and after considering the possibility that it was for a college production, puts forward two arguments that rule this out. The cast of Dido includes three parts (Ganymede, Ascanius, Cupid) that must be played by much smaller boy actors if they are to be plausibly "dandled" on the laps and knees of bigger boys playing adult roles. This is a realistic ask for "a London choirboy company like the Children of the Chapel" where the boys might range from the age of six to teenagers.17 Whilst other plays are known to have been performed at Cambridge in the 1580s that also include boy parts, the specific stage directions in Dido says Wiggins preclude the possibility that these parts could be played by even the smallest of Cambridge students. His second argument is simply that the play is written in English, whilst "during Marlowe’s student days, Latin was the exclusive medium of academic drama at Cambridge". In support of this, an apologetic reply is quoted from the University authorities to a request by Lord Burghley to perform a play in English for a royal visit in 1592: the University "do[es] find our principal actors very unwilling to play in English ... English comedies, for that we never used any, we presently have none".18

Having discounted these options, Wiggins argues that the play belongs "exactly where the title page places it, in the repertory of the Children of the Chapel".19 The history of the Children of the Chapel and the Children of Paul's is not at all clear after their 1984 court performances. There may have been some kind of merger under the patronage of the Earl of Oxford, whose secretary was John Lyly. Both companies still appeared at times under their individual names, although there is no extant record of the Children of the Chapel appearing at the London theatres after 1984, only on tour. However, Wiggins wonders if a reference in a January 1988 letter complaining of the proliferation of playbills in London including some in the name of the Earl of Oxford, may refer to the merged boys company: "it need not surprise us that they called themselves the Children of the Chapel Royal in the provinces, but emphasised their connection with the Earl of Oxford in the capital".20

The stage directions indicate to Wiggins that Dido was "written for a playhouse equipped with a discovery space and a stage trap, not devised for a touring company to perform".21 He further identifies an anonymous play, The Wars of Cyrus, which was also printed in a 1594 Quarto edition advertising that it was "played by the children of her Maiesties Chappell". The play is of a near identical length to Dido, with similar casting and theatrical staging requirements. Wiggins 'joins up these dots' and proposes a hypothesis that after 1584 "the Chapel Boys had the use of a theatre, well-equipped by the standards of the time and presumably in London".22 Marlowe "was probably approached in 1588, after he had written the Tamburlaine plays, and after Nashe had come to London. If this is a true story, then Marlowe’s biographers will have to rethink their understanding of his professional career. Dido can no longer be sidelined as an immature work distinct from the main run of the plays".23 Wiggins thus concludes that this was not Marlowe's first play, but was rather penned after Tamburlaine, most likely at a similar time to Doctor Faustus (which he dates as 1588).24

In the latest Revels edition of the play, disputes Wiggins' later dating along with any significant contribution by Nashe, firmly of the opinion that Dido is a product of Marlowe's student days. She dates it to "1584 or 1585", when Marlowe was studying for his MA and had "more opportunity to write", not least due to having "more leeway with attendance".25 Such opportunities would also be afforded by University "vacations and closures during epidemics", as well as Marlowe's purported periods of absence based on the Corpus Christi buttery accounts first transcribed and analysed by Bakeless.26

Regarding who the play was intended for, Lunney suggests Marlowe may have written Dido "in the expectation that the children's companies would keep performing, including at court", even if that proved not to be the case (fellow Canterburian Lyly's Galatea was registered in 1585 but not performed at court until 1588).27 She fails to find any credence beyond the circumstantial in Wiggins proposal that the play's similarities to The Wars of Cyrus indicate the two Chapel Children plays were both commissioned in response to the success of Tamburlaine.28 Rather she finds "continuities [of] subject matter and theme" between Dido and plays written for children's companies in the first half of the 1580's such as Lyly's first two plays Campaspe and Sapho & Phao (both published in 1584, stating they had been played by the Children of Paul's), and Peele's The Arraignment of Paris (performed at court and by the Chapel Children in 1584). Marlowe may also have been inspired by the success of the Latin version of Gager's Dido at Oxford in June 1583, which was notable enough to be mentioned by Stowe.29 Lunney adds that the "verbal style and dramatic structure" of the play may also be consistent with it being written for a children's company. For example, characters referring to each other by name as noted by Oliver, was perhaps intended to "indicate cues or embedded instructions" to child actors.30

In all of this there is no clear agreement, and without the uncovering of any new clearcut evidence that precisely dates the writing of Dido, Queen of Carthage, the to-and-fro of academic debate on the subject will likely continue.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: Tucker Brooke opines "No question in Marlowe criticism offers greater difficulties than those which concern the date and authorship of the Tragedy of Dido." in [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.387. Back to Text

- Note 2: , Marlowe in Miniature: Dido, Queen of Carthage and the Children of the Chapel Repertory, Chapter 3 in [Marlowe-Commerce] p.45. Back to Text

- Note 3: [Chambers-ElizStage] Book III, Section XII.B.ii (Vol. II) pp. 36-42 covers this period of the company's history in detail. Back to Text

- Note 4: [Wiggins-Didodate] pp.531-4. Back to Text

- Note 5: , The Influence of Christopher Marlowe on Shakespeare's Earlier Style (Cambridge, 1886) pp.29, 70-1. Back to Text

- Note 6: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.387. See section under Authorship for a summary of reworkings of some lines in other Marlowe plays. Back to Text

- Note 7: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.387-8. Back to Text

- Note 8: , Shakespeare and the Rival Traditions (New York, 1952) pp.66-68. Back to Text

- Note 9: , Evidence for Dating Marlowe's Tragedy of Dido, Chapter 15 in Studies in the English Renaissance Drama (Ed. Josephine W. Bennett, Oscar Cargill, Vernon Hall, New York University Press, 1959) p.239. Back to Text

- Note 10: , Suffering and Evil in the Plays of Christopher Marlowe (Princeton University Press, 1962) pp.75-6. Back to Text

- Note 11: , English Tragedy Before Shakespeare (Methuen Young Books, 1961) p.162. Back to Text

- Note 12: [Revels-Oliver] p.xxviii. Back to Text

- Note 13: [Revels-Oliver] p.xxix. Back to Text

- Note 14: [Revels-Oliver] p.xxix-xxx. Back to Text

- Note 15: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.526. Back to Text

- Note 16: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.523. Back to Text

- Note 17: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.527. Back to Text

- Note 18: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.530. Back to Text

- Note 19: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.531. Back to Text

- Note 20: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.533. Back to Text

- Note 21: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.539. Back to Text

- Note 22: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.540. Back to Text

- Note 23: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.541. Back to Text

- Note 24: [Wiggins-DidoDate] p.541. The play also appears in Volume II of & [BritDrama-Catalog] under 1588. Nashe is recorded as attending lectures at St. Johns in 1588, and is generally considered most likely to have left Cambridge for London in the summer of that year e.g. [Nicholl-Cup] pp.37-38. As Marlowe graduated MA the previous summer, the year from summer 1587 to summer 1588 is perhaps the only time under consideration when Nashe and Marlowe were not resident in the same city, and therefore perhaps the period least likely for them to have collaborated on Dido as Wiggins believes. His dating might be assumed therefore to be the second half of 1588. Back to Text

- Note 25: [Revels-Lunney] p.17. Back to Text

- Note 26: [Bakeless-Man] pp.78-80, Appendix A pp.334-347. [Revels-Lunney] (p.19) notes: "In 1584 Marlowe was absent from Cambridge from July to December, returning in December for a few weeks before leaving again." Back to Text

- Note 27: [Revels-Lunney] p.18. Lunney opines (pp.19-20) that Marlowe "would not have been unaware of the example of John Lyly, also a son of Canterbury, who had achieved celebrity with his two Euphues books in 1578-80, while Marlowe was at school with Lyly's younger brother." Back to Text

- Note 28: [Revels-Lunney] p.19. Back to Text

- Note 29: [Revels-Lunney] p.20. Back to Text

- Note 30: [Revels-Lunney] p.22. Back to Text