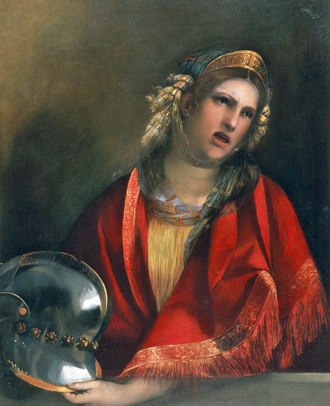

Dido Queen of Carthage

Themes in the Play

Marlowe's Imprint

The main subject matter and some of the basic themes within Dido, Queen of Carthage are of course inherited from source, which Marlowe adheres to closely for the main story-line. The main interest for the Marlovian scholar is why Marlowe should have picked this story to adapt for the stage, and then to examine the changes and additions that the playwright has made in his dramatisation in the hope that it might tell us something about Marlowe's ideas.

It is difficult to answer the first question. Perhaps Marlowe may have had some familiarity with the source which played a part in his choice. At a high level the concept of God(s) and their relationship with Man is an idea that clearly interested Marlowe, and is one that plays a key role in Tamburlaine and Doctor Faustus as well. If we could be more certain as to the dating of the play, and perhaps who Marlowe was writing the play for, then we might be able to make some better inferences regarding his choice of material.

In contrast, the close relationship to the source of the play, Aeneid, allows us to see in some detail exactly what Marlowe has added and what he has changed. very well sums up the essential themes of the story, and the slant that Marlowe brings to his play. "The theme of the play is not so very different from that of Book IV of the Aeneid: betrayal in love as the price paid for obeying the behest of the Gods; and the difference is, of course, that Marlowe is much less sympathetic to the behests of the Gods, so that humans are less the dignified agents of divine wisdom and more the victims of the politics of Olympus".1

The Petty Gods

Marlowe subtly depreciates the importance of the Gods. Twice Jupiter dispatches his messenger Hermes to remind the mortal Aeneas of his important mission, namely the founding of Rome. His love for Dido must not distract him. "Why cosin stand you building Cities here, and beautifying the empire of this Queene while Italy is cleane out of thy minde?" [V.i.27-8] asks Hermes. And yet at the start of the play (in a scene which is solely Marlowe's creation) we see Jupiter, King of the Gods no less, completely infatuated by Ganymede and consequently oblivious to the fact that Aeneas' mission has quite literally been blown of course as a result of Juno's plotting. It takes Venus' intervention to inspire Jupiter to action, and later it is perhaps only Iarbus' prayers that again bring the God's attention to the dallying Aeneas.

The vengeful soliloquy by Juno, who, after finding Ascanius hidden in the grove, muses on murdering the child, is also Marlowe's work. There is a deep enmity between Juno and Venus, but the playwright accentuates the Machiavellian pact formulated by the two Goddesses to raise the storm that will lead Aeneas into the cave with Dido; the expected outcome is in the interest of both Juno and Venus.

The scene in which Cupid somewhat cruelly touches the nurse with his dart, and inspires the eighty year old woman to start dreaming of love and taking a husband, is another scene (IV.v) added by Marlowe. Cupid's childish amusement, as well as the opening scene in which "Jupiter has been seen cajoling a cheeky, teasing Ganymede", suggest to that "these Gods are petty childish humans who have all the worlds to play with. In other hands, the gods as dramatis personae in such a context would be darkening powers, baleful and menacing; but with Marlowe they are merely part of the exuberant power-play".2

Marlowe Challenging Convention

Marlowe has also added substantially to the solitary example of unrequited love in Aeneid. As well as Dido's ultimately fruitless passion for Aeneas, Marlowe introduces four other 'victims' of unreturned love: Jupiter besotted with Ganymede; Anna's failed pursuit of Iarbus, who in turn is continually rejected by Dido, and finally and most bizarrely the old nurse's sudden desire for the young boy, Cupid.

sees Marlowe challenging and inverting convention through these additional relationships. "Lovers [in Dido] rarely conform to conventional codes of behaviour: men pursue boys, females woo males; and old crones seek to seduce pink-faced lads. Of the five amours, only one - Iarbus' rather drab suit to Dido - adheres to conventional sex/gender etiquette".3 Marlowe's ambiguous moral framework, as in his other plays, has inspired a wide range of responses.

Romantic or Moralistic?

But perhaps it is the core of Marlowe's play that has sparked the most debate, the "ambiguous treatment of the two protagonists," Dido and Aeneas, which "has aroused diverse, even antipodal responses".4 Is Marlowe taking sides? "There have been many different attitudes to Marlowe's portraits of Dido and Aeneas. These interpretations differ so much that they cannot all be in accord with Marlowe's intention".5

The two main conflicting interpretations, the "romantic, pro-passion," and the "moralistic, pro-duty" reading are again well summarised by , who also cites examples of commentators in each camp.6

In the former case, Marlowe is sympathising with Dido, the tragic and eponymous heroine, whilst simultaneously lowering our opinion of Aeneas through his portrayal. The Trojan swears his love to Dido, but betrays that promise via his (intended) departure from Carthage - not once as in , where no vow was ever made, but twice. His excuses after the first failed attempt to leave are particularly weak. His account of the fall of Troy also raises question marks about Aeneas' honour towards women (his failure to save his wife Creusa, Cassandra and Polyxena) and anticipates his desertion of Dido. Also, through his portrayal of the Gods as exhibiting human flaws, Marlowe is implicitly undermining Aeneas' ultimate justification for his eventual departure to Italy.

A pro-duty interpretation rather cites the comic or farcical aspects of the play (Jupiter's "dandling" of Ganymede, Dido's reaction to being struck by Cupid's dart, likewise the Nurse's reaction, and the anti-climactic triple suicide) as Marlowe deliberately undermining the tragic nature of the play. Dido's love is not real, but rather artificially induced by Cupid, and thus Aeneas is ultimately right to decide in favour of his duty. Rather than callously betraying his promise to Dido, Aeneas is instead the victim of a moral dilemma, and his return to Dido after his first abortive departure rather demonstrates his integrity in this no-win situation.

Perhaps, as concludes, Marlowe did in fact consciously offer up these "two antithetical interpretations".7 Marlowe could be provoking his audience into considering both sides of the story, debating apparently opposing standpoints as his University training may well have taught him to do, but without actually providing a decisive resolution.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: [Revels-Oliver] p.xlv. Back to Text

- Note 2: [Steane] p.47. Back to Text

- Note 3: , chapter 12 of [Cambridge-Companion] p.197. Back to Text

- Note 4: , chapter 12 of [Cambridge-Companion] p.195. Back to Text

- Note 5: [Revels-Oliver] p.xxxix. Back to Text

- Note 6: Chapter 12 of [Cambridge-Companion] pp.197-9, where cites [Steane] and ("Marlowe's Dido and the Tradition" in Essays on Shakespeare and Elizabethan Drama, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 1962) as being in the romantic camp, whilst (The Marlovian World Picture, Mouton, The Hague, 1974 pp.38-58) and ('Love Kindling Fire', Institut fur Englishe Sprache und Literatur, Salzburg, 1977) were in the pro-duty camp. [Revels-Oliver] also offers a summary of these two viewpoints pp.xl-xliv. Back to Text

- Note 7: , chapter 12 of [Cambridge-Companion] p.199. Back to Text