Marlowe's Works

Prologue

A professional writing career that would last just six short years exploded dramatically onto the London stage in 1587 with Tamburlaine "threatning the world with high astounding tearms".1 The startling success, distinctive bold style and "generall welcomes Tamburlain receiu'd when he arriued last vpon our stage"2 inspired Christopher Marlowe to write a sequel in double quick time. He would go on to write at least five further (often pioneering) plays, most notably his Doctor Faustus and the history of Edward the Second which are still regularly performed today. The Elizabethan actor Edward Alleyn was famous for playing Marlowe's leading roles at The Rose theatre on Bankside, certainly Tamburlaine, Faustus and Barabas in the tragi-comic play The Jew of Malta, his "scenical strutting and furious vociferation"3 synonymous with these high-aspiring characters who delivered their lengthy soliloquies in blank verse to large rapt audiences.

The tragedy of Dido, Queen of Carthage is far more than a dramatisation of Virgil's Aeneid, but has caused much debate as to its date of composition (an early University effort later updated?) and the extent of Thomas Nashe's input (Marlowe's friend credited jointly on the posthumous title page). Marlowe's bloody take on contemporary European religious events, The Massacre at Paris, written later in his short career, is unfortunately only extant in a severely mutilated form. He has also left us with some beautiful verse, the best-known being Hero and Leander, alas unfinished at his death in 1593. Turning all forty-eight of Ovid's Elegies (the Amores) into elegiac couplets was a significant undertaking reflected perhaps in the slightly uneven results, whilst Marlowe's blank verse translation of the first book of Lucan's Pharsalia is at times very powerful.

Brief synopses of Marlowe's plays and poetry can be found below, with more detailed overviews to follow, starting with Dido, Queen of Carthage.

Published Plays

| Ref | Title | First Published | Stationers' Register | Text | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

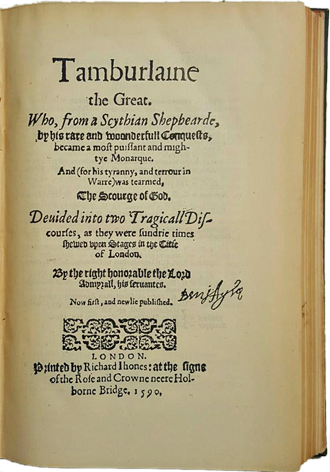

| [Marlowe-Tamburlaine] | Tamburlaine the Great ... Devided into Two Tragicall Discourses | Richard Jones, London 1590 (Octavo edition of Parts I & II) | 14 Aug 1590 [SRO3094] | EEBO | Synopses of Tamburlaine Pt I and Tamburlaine Pt II | Wikipedia |

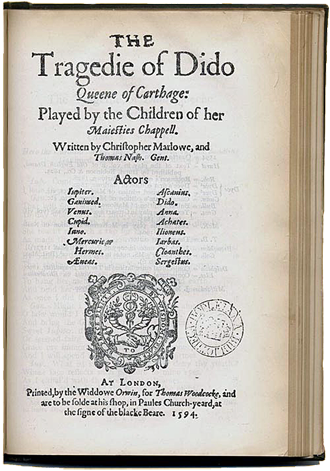

| [Marlowe-Dido] | The Tragedie of Dido Queene of Carthage | Thomas Woodcock, London 1594 (Quarto) | No entry | EEBO | Overview of Dido |

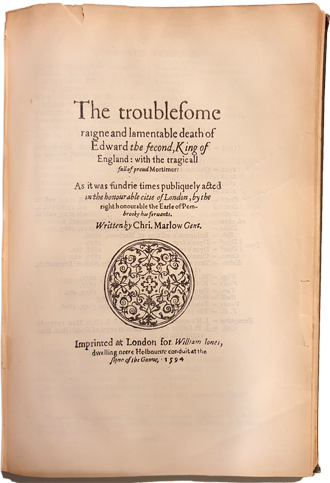

| [Marlowe-EdwardII] | The Troublesome Raigne and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second | William Jones, London 1594 (Octavo in quarto-form) | 06 Jul 1593 [SRO3497] | EEBO | Synopsis of Edward II | Wikipedia |

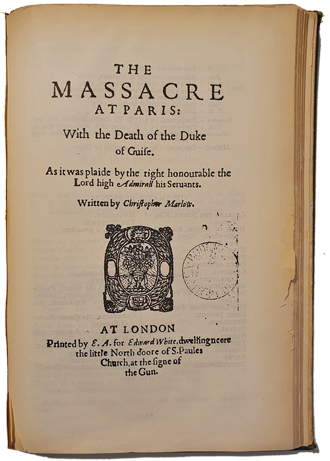

| [Marlowe-Massacre] | The Massacre at Paris: With the Death of the Duke of Guise | Edward White, London (Undated, likely between 1594-1606; Octavo) | No entry | EEBO | Synopsis of The Massacre at Paris | Wikipedia |

| [Marlowe-Faustus] | The Tragicall History of D.Faustus | Thomas Bushell, London 1604 (Quarto, the so-called 'A-Text') | 07 Jan 1601 [SRO4383] | EEBO | Synopsis of Dr Faustus | Wikipedia |

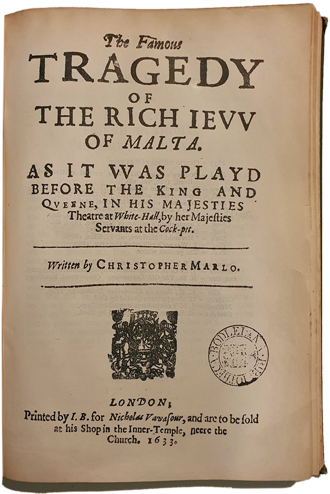

| [Marlowe-JewOfMalta] | The Famous Tragedy of the Rich Jew of Malta | Nicholas Vavasour, London 1633 (Quarto) | 17 May 1594 to Nicholas Ling and Thomas Millington [SRO3612] | EEBO | Synopsis of The Jew of Malta | Wikipedia |

Published Poetry

| Ref | Title | First Published | Stationers' Register | Text | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Marlowe-HeroLeander] | Hero and Leander | Edward Blount, London 1598 (Quarto) | 28 Sep 1593 to John Wolfe [SRO3514] | EEBO 4 | Synopsis of Hero & Leander | Wikipedia |

| [Marlowe-Elegies] | All Ovids Elegies | Published at Middleburgh (Holland) by 1599 5 (Octavo) | No entry | EEBO | Synopsis of Ovid's Elegies | Wikipedia |

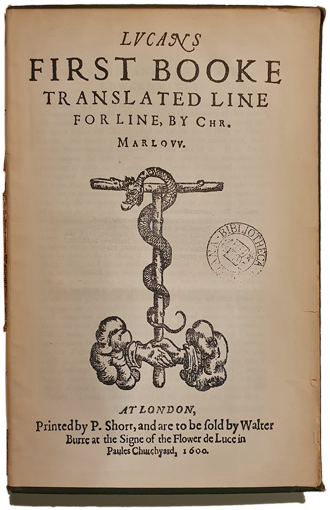

| [Marlowe-Lucan] | Lucans First Booke | Thomas Thorpe, sold by Walter Burre, London 1600 (Quarto) | 28 Sep 1593 to John Wolfe [SRO3513] | EEBO | Synopsis of Lucan's First Book | Wikipedia |

Dido Queen of Carthage

This dramatisation of the tragic love story of Dido and Aeneas was based heavily on 's Aeneid, a fact which led many early commentators to dismiss the play as little more than a University exercise in Latin translation. But whilst the playwright stuck tightly to his source in places, he has also added significant scenes, sub-plots and character tweaks that bear a distinctive Marlovian air, not to mention some beautiful verse in places. There is perhaps a hint of Marlowe's atheism in his presentation of the Gods and Goddesses with plenty of human flaws. Does the author sympathise more with Dido, presenting Aeneas more the betrayer, leaving for Italy with weak excuses after professing his love? Or is Aeneas justified in following his call to duty because Dido's love is falsely induced by Cupid's dart? As usual, Marlowe may be ambiguously playing both sides.

There are no records extant of contemporary performances of the play, which survives only in a single quarto edition published the year after Marlowe's death with a title page that has sparked much debate since. The statement that the play was "played by the Children of her Maiesties Chappell" has caused puzzlement as there is no record of the boys' company performing at court or the Blackfriars theatre after 1584, with only some occasional touring appearances recorded that are unlikely to merit such a prominent advertisement in print. This is one factor that makes the dating of the play very difficult: is it an early student effort somehow taken on by the prestigious Children of the Chapel Royal, or a mature effort performed by them at a time and place of which we no longer have any record? There are hints from an inventory of props and costumes by Henslowe that the play may have been subsequently revived at The Rose in 1598.

Even more intriguingly, the authorship of the play is jointly attributed to both Marlowe and his friend Thomas Nashe on the 1594 title page. On a practical level this is feasible as the pair were, with the exception of one year, co-located in Cambridge and then London from 1582 onwards. Was it genuinely a joint collaboration, or was Nashe's contribution limited to an editorial role as he saw his dead friend's play into print, perhaps including an elegy written for Marlowe but now lost? Whilst increasingly sophisticated computerised textual analysis has recently tended towards attributing the entire play to Marlowe, we may conclude that the strong presence of the Marlovian style and subject matter along with a sprinkling of variations on his most famous lines confirm Marlowe at the very least as being responsible for a sizable portion of the play.

You can also read this website's more detailed overview of Dido, Queen of Carthage.

Tamburlaine the Great Part I

Just out of University in the summer of 1587, Marlowe's play dramatising the rise to global power of the "Scythian Shephearde" took the London stage by storm. The ambitious Tamburlaine is being attacked by the powerful Persian emperor Mycetes, but persuades the latter's brother Cosroe to lend his army's help in return for a place on the throne. After victory, the Scythian reneges on his promise, taking control himself, and also wooing the beautiful Zenocrate, daughter of the Egyptian soldan. Unsated, Tamburlaine ruthlessly defeats Bajazeth, imprisoning the Turkish emperor in a cage, and humiliating him to the extent that he commits suicide. Africa is next to be conquered, and it seems only Zenocrate can curb the Scythian's bloodlust, successfully pleading for her father to be spared as Tamburlaine trains his sights on Damascus. The play ends with the pair's marriage, Tamburlaine also crowning Zenocrate as Empress of Persia.

The legend of the mongol conqueror Timur, or Tamerlane (b.1320's, d.1405) was well established and indeed documented in western Europe by the end of the sixteenth century. An account of Tamburlaine's life in Silva de Varia Lección (A Miscellany of Several Lessons) by the Spanish historian Pedro Mexia (first published in 1540) provided Marlowe with the basis for his plot via various translations, two in English by George Whetstone (published just the year before)6 and Thomas Fortescue,7 and one in Latin by Pietro Perondinius,8 the latter providing some description of Tamburlaine's character.9 The sources name only Tamburlaine and the sultan of the Ottoman empire, Bajazeth, with the minor characters in the play largely of Marlowe's invention.

The Admiral's Men likely debuted the play, with Edward Alleyn excelling in the title role as the "scourge and wrath of God, the onely feare and terrour of the world" [III.iii]. The strutting, bombastic style and the new playwright's innovative blank verse made quite an impact, and was much imitated. Robert Greene was soon mocking his own inability to make his "verses jet upon the stage in tragicall buskins, euerie worde filling the mouth like the faburdern of Bo-Bell, daring the God out of heauen with that Atheist Tamburlan", and referring to "such mad and scoffing poets, that haue propheticall spirits bred of Merlin's race".10 The character and plays were still much in the public's mind six years later in 1593 when an anonymous libel was fixed to the wall of the Dutch Church in Broad Street, London, threatening violence to the "stranger" immigrant community and signed "per Tamburlaine".11

Tamburlaine the Great Part II

The impact and plaudits that "Tamburlain receiu'd when he arriued last vpon our stage hath made our Poet pen his second part" without delay.2 If a letter by Philip Gawdy to his father is describing a tragic accident at a performance of this play by "my L. Admyrall his men", then Tamburlaine the Great Part II was already on the London stage by 16 November 1587. Gawdy describes an actor who fired a "callyvers" at "one of their fellowes" tied to a post, but the gun "swerved" and ended up killing a child and a pregnant woman.12 The action fits with Theridamas and others shooting the Governor of Babylon in Scene V.i.

In this sequel, Tamburlaine continues his brutal and unrelenting quest for world domination. He hopes his sons Calyphas, Amyras and Celebinus will follow in his footsteps, but the first has no wish to fight. Callapine, the son of Bajazeth, has escaped his imprisonment and rallies a force to exact revenge. Tamburlaine is victorious once more, but kills Calyphas in a rage when he learns that his son stayed in his tent during the battle. The Scythian humiliates the vanquished kings by making them pull his chariot, chiding them: "Holla ye pampered Jades of Asia! What, can ye draw but twenty miles a day?" [IV.iii.1-2] His attempts to conquer Babylon meet brave resistance before further acts of barbarity see Tamburlaine triumph. He has the Governor shot despite offering up the city's treasury. Men, women and children are tied up and thrown into a lake. He burns the Qu'ran whilst claiming to be greater than God, a scene that likely inspired Greene's reference to the "Atheist Tamburlan".10 It is only sickness that finally defeats the aged emperor, but he still has time to show "his boies" on a map how they may "finish all my wants" and conquer the remaining parts of the world after he has gone. Having crowned his son Amyras in his place, his final words are to declare "Tamburlaine, the Scourge of God must die." [V.iii]

Both parts of the play were soon in print, the two "commicall [!] discourses of Tomberlein the Cithian shepparde" entered in the Stationers' Register on 14 August 1590 to Richard Jones, who duly published a combined Octavo edition that same year. This pair were the only plays of Marlowe's published during his lifetime, but he had certainly announced himself. There were further editions re-printed for Jones in 1592 and 1597, before Edward White published separate quarto editions of each part in 1605 and 1606 respectively. Although the brash, bombastic style of Marlowe's break-through stage successes would fall out of fashion over time, the pair of plays were still popular enough for Henslowe to put on twenty-two performances at the Rose regularly between August 1594 and November 1595, more than a year after the playwright's death.13 Although there is no record of any subsequent performance at the Rose (Henslowe's Diary of performance receipts ends in 1597), items for Tamburlaine are still listed in an inventory of the Admiral's Men properties and costumes in March 1598.14

Doctor Faustus

Without doubt Doctor Faustus was Marlowe's most successful play, boasting some of his most famous lines and telling the story of the legendary German scholar who makes a pact with the devil to satisfy his thirst for knowledge and magic powers in exchange for his soul. As with some of the other plays, it is difficult to pin down the exact date Marlowe wrote it. He used as his source the so-called "English Faust Book"15 of which the earliest extant edition is dated 1592 but which was perhaps not the first. A number of references and allusions to Marlowe's play in other literature of the time may suggest an earlier date of composition, perhaps 1588-89 when plays about "magicians and their tricks" were very much in vogue.16

Faustus, we learn initially from the Chorus, is a Doctor of Theology at the University of Wittenberg, but the opening scene finds him bored with the career options available. What he really craves is the "metaphisickes of magicians, and necromanticke books". Ignoring warnings from the Good Angel, and egged on by the Evil Angel, Faustus summons a devil in the shape of Mephistopheles ("servant to great Lucifer") who asks "what wouldst thou have me do?" Faustus signs a deed in his own blood at midnight, granting that his every demand of Mephistopheles shall be met, but in return bequeathing his soul to Lucifer after twenty-four years. Faustus uses his new powers to ask for a wife, books of "spels and incantations", and knowledge about nature, heaven and hell, and the secrets of the universe. As Faustus wavers, Lucifer appears to remind him of his promise, and conjures up the seven deadly sins "in their proper shapes" to inspire Faustus by showing him that "in hell is all manner of delight".

Mephistopheles takes Faustus flying "in a chariot burning bright, drawne by the strength of yoky dragons neckes" on a whirlwind tour of Germany, France and Italy and thence to Rome where, invisible, the pair play tricks upon the Pope. A humorous sub-plot is entwined in which Robin and Rafe (Dick in the B-text) find a book of Faustus' and conjure a spirit to save them after stealing a tavern goblet, only to have Mephistopheles turn them into animals. Lucifer's agent quickly returns to Faustus' side at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor where Alexander the Great is magically made to appear. Faustus' time is nearly up, but he accedes to one last request from a group of scholars to summon up the beautiful Helen of Troy. Alone with Mephistopheles, he asks that Helen, "the face that launch a thousand shippes," appear once more for his own benefit, whereupon she makes Faustus "immortall with a kisse, her lips suckes forth my soule". The doctor retires alone to his study, and as the clock ticks down to midnight he pours out a terrified soliloquy of remorse and repentance. But it is too late, and his final words describe his damnation and the hellish scene awaiting him: "Adders and serpents, let me breathe a while: Vgly hell gape not, come not Lucifer, Ile burne my books, ah Mephistopheles… [Exeunt with him]".

Doctor Faustus must have been a popular staple on the London stage during Marlowe's lifetime. Although there are no references in Henslowe's Diary of a performance before September 1594, there are 25 performances in total recorded regularly thereafter up until October 1597 at the end of those records.17 More than forty years later, cited accounts of playgoers who witnessed "the visible apparition of the Devill on the Stage at the Belsavage Play-house" on Ludgate Hill during a performance of the "History of Faustus" which would have been at least before 1594.18 The play itself did not appear in print until 1604, when Thomas Bushell published the so-called A-text. John Wright reprinted essentially that same version twice more in 1609 and 1611, before publishing an enlarged version in 1616 with some 640 more lines (the so-called B-text). Whilst it was only the next edition (B2) published in 1619 that first advertised "new additions", and despite Christopher Marlowe's name always appearing as sole author on the title page, it has long been thought another writer may have collaborated with Marlowe in the original writing of the play (i.e. separate from any later additions), likely responsible for some of the comic scenes.19

The Jew of Malta

Although the play is not often performed nowadays, partly due to a single extant text of uneven quality as well as the antisemitic stereotypes portrayed, The Jew of Malta was hugely popular with Elizabethan audiences. During the period that Henslowe kept a record in his diary (1592-7), it was performed more than any other play, a total of 36 times between 26 February 1592 and 21 June 1596 whilst bringing in consistently high receipts.20 A particularly intense period of performance followed the death sentence for alleged treasonous offences of the Queen's physician Dr Roderigo Lopes, who was accused of being "a perjured, murdering villain and a Jewish doctor worse than Judas himself".21 The play was performed by different companies, perhaps indicating that Henslowe himself owned the play. The cauldron used in the play is listed in an inventory of properties taken in March 1598, and Henslowe records significant expenditure on items and costumes for the play in May 1601, perhaps indicating a revival. 22

The opening scene finds "Barabas in his Counting-house, with heapes of gold before him" revelling in having amassed "infinite riches in a little room". He is awaiting the return of his trading ships when he learns of "a fleet of warlike Galleyes ... come from Turkey", the Turkish emperor having sent his son Selim-Calymath to collect payment of a "ten yeares tribute that remains vnpaid". Ferneze, the Christian Governor of Malta, raises a 50% tax on all the Jews of Malta to pay the tribute, but after an angry exchange with Barabas, orders that all his wealth be seized and his house be converted into a nunnery. Barabas has hidden 10,000 gold coins and a large stash of jewels under the floorboards, and convinces his daughter Abigail to enlist as a nun to retrieve it. Aided by his slave Ithamore, Barabas embarks on a trail of murderous revenge. He tricks the governor's son and his friend into killing each other in a duel over his daughter. When Abigail returns to the nunnery in disgust, an angry Barabas poisons all the nuns including her. He strangles a friar and frames another for the murder, and then poisons Ithamore and a courtesan to whom his slave had spilled his secrets. Barabas plots with the Turks to lay siege to Malta, but when they do so and make him Governor, he switches to conspire with the Christians. He plans a trap for the Turks involving a cauldron, but Ferneze double-crosses him and it is Barabas who falls into the pot and is boiled alive. The play ends with Ferneze informing Selim-Caymath that all "all thy souldiers [are] massacred" and that he he will be held hostage on Malta as protection against further Turkish attacks.

As Machevil in the prologue implies that the Duke of Guise's death on 23 December 1588 was quite recent ("And now the Guise is dead...") and given that the play was in performance before February 1592, it seems likely Marlowe wrote The Jew of Malta around 1589-90. The only extant text was published over forty years later in 1633, and had likely undergone some revision since it left Marlowe's pen. It is possible there were earlier published edition(s) of the play, now lost.23 The first two acts are of good quality, but as Tucker Brooke laments, "the vigorous flow of tragic interest and character portrayal with which the play opens, wastes away amid what, for the modern reader, is a wilderness of melodrama and farce".24 Despite the mixed quality of the text, there are no claims for joint authorship and "no signs of revision by a later dramatist".25 Marlowe does not seem to have used any particular source for The Jew of Malta. The Turkish siege of Malta in 1565 provides a basic setting, but little of the action in the play corresponds to those historic events. There were other documented Turkish sieges that Marlowe could have drawn on for details,26 and there may have been other source material now lost. mentions a play called "The Jew" in The School of Abuse (1579) of which there is no other record.27

Edward the Second

The Troublesome Raigne and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second was, according to , the "maturest" of Marlowe's plays, "the best preserved of the poet's tragedies, and much the most perfect in all matters of technical skill".28 It was a pioneering early example of dramatising English history for the London stage, which along with the Shakespearean War of the Roses tetralogy set the standard for such plays that followed. Like Shakespeare, Marlowe's primary source for his history was 's Chronicles of England,29 but he also included details only found in other historic sources.30 The subject matter with its homosexual undertones clearly appealed to Marlowe. A weak king doting on male favourites, more interested in esoteric pleasures than conducting the difficult affairs of state amidst a feuding nobility, is a theme that (re)appears in the second half of The Massacre at Paris in the shape of the French king, Henri III.

The play dramatises the entire twenty-year reign of Edward II but with the events much compressed by Marlowe and sometimes rearranged for the purpose of the theatrical narrative. In the opening scene we find that Edward, newly crowned after his father's death, has invited Gaveston to return from France where Edward I had banished him "and share the kingdom with thy deerest friend." Gaveston is only too happy to "be the fauorit of a king", desiring "wanton Poets, pleasant wits, musitians, that with the touching of a string may draw the pliant king which way I please". The powerful English nobles are less happy with the titles, wealth and influence poured by the doting king on "base and obscure Gaueston", who is soon forced once more into exile in Ireland. It is Queen Isabella, spurned by her miserable husband, who plots with Mortimer to have Gaveston recalled, so that she might regain the king's favour and because if he were back in England "how easilie might some base slaue be subornd, to greet his lordship [Gaveston] with a poniard". The king is over-joyed at the return of his love, but Gaveston is soon infuriating the other nobles, who are further angered by defeat at Bannockburn (actually 1314 after Gaveston's demise) and the King's reluctance to pay a ransom for the captured Mortimer Senior. The barons conspire to capture Gaveston, and Warwick kills him before he can see Edward again. In revenge, the king has Warwick and Lancaster executed.

Edward takes solace in his new favourite Spencer, who supported the king during Gaveston's last days. Isabella, having given up on her husband, takes Young Mortimer as a lover and the pair now actively plot against her husband. She travels to France with her young son the prince, but the French king refuses to provide an army. Sir John of Hainault, however, offers "comfort, money, men and friends". Isabella and Mortimer return to England, their forces prevail, and Edward flees and takes refuge at Neath Abbey where he is betrayed by a mower (aptly carrying a scythe or "welsh hook"). Edward is imprisoned first in Kenilworth Castle where, after alternate fits of rage and melancholy, he resigns the crown. The Spencers are executed. The king is moved to Berkeley, kept in torturous conditions ("in mire and puddle have I stood this ten dayes space") and deprived of sleep ("one plaies continually vpon a Drum"). Mortimer begins to panic, fearing that "the commons now pity him". He employs the fiendish Lightborne (who has killed before) to secretly murder Edward such that "none shall know which way he died". Edward realises his fate and fearfully confronts Lightborne, who murders him with a "a spit" which is "red hote". But Mortimer has secretly ordered the king's jailers Matrevis and Gurney to kill Lightborne once the deed is done. The pair then flee, but "false Gurney hath betraide" Mortimer and the young Prince (now King Edward III) knows the truth of his father's murder. He orders that Mortimer be executed: "bring him vnto a hurdle, drag him foorth, hang him, set his quarters vp, but bring his head back presently to me". Isabella pleads for her lover's life, but her son holds her responsible too, and imprisons her in the Tower. The play ends with Edward III ordering his father's hearse be fetched so he can "moorne [his] sweete father heere".

Once more it is difficult to establish a precise date when Marlowe wrote Edward the Second. The title page when first published in 1594 stated that the play had been "sundrie times publiquely acted in the honourable citie of London, by the right honourable the Earle of Pembrooke his seruants", most likely in December 1592, January 1593 or in 1594.31 Marlowe's maturer style and the seeming indebtedness by/to other plays of the period suggests perhaps a date in 1591 or early 1592.32 Pembroke's Men did not perform at Henslowe's theatres until the end of the century, and there is no mention of any performance of Edward the Second in his diaries. The play was registered by William Jones on 06 July 1593 [SRO3497], little more than five weeks after the playwright's death, the quarto-form Octavo first edition (of which only two copies survive)33 not being published until the following year. Three further editions were published in 1598, 1612 and 1622, the last informing us that the play had been revived by "the late Queenes Maiesties Seruants at the Red Bull in S. John's streete".

The Massacre at Paris

Quite possibly Marlowe's final play, The Massacre at Paris is only extant in what seems to be both an abridged and 'reported' text preserved via a single undated Octavo version published by Edward White at some point between the playwright's death and 1606. The result is a play text approximately half the length of Edward the Second, The Jew of Malta, and each part of Tamburlaine, mostly comprised of fast moving and bloody action, but lacking for the most part in much depth of characterisation or good quality verse. The so-called 'Collier Leaf' portrays a much fuller version of one scene, but the apparent discovery of this manuscript sheet in the mid-1820's by the historian and forger John Payne Collier casts a significant doubt on its authenticity. That only a corrupt text survives is a huge pity, for there is much of interest in Marlowe's take on the recent French Wars of Religion, and the very rare and brilliant modern production by The Dolphin's Back company at The Bankside Rose in 2014 gives some sense of just how breath-taking the full play could have been.

The play is unusual in addressing contemporary European history, and indeed a sensitive political situation on England's own doorstep. The first half of the play dramatises the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in August 1572, instigated by the French royal rulers (including Catherine de' Medici) and Catholic nobles (including the Duke of Guise) which saw the systematic murder and execution of thousands of protestant Huguenots in the French capital. Marlowe has Guise murder the old protestant Queen of Navarre with a poisoned glove before the wedding of her son Henri of Navarre to the French King's sister, Margaret, an event that prefaces the massacre. The playwright brings the story of the French Wars of Religion up to date through the reign of Henri III and the three-way war between that King, Guise and Navarre. The climax of the play covers some very recent history with the murder of the Duke of Guise and his brother in December 1588, and the subsequent murder in turn of Henri III by a Dominican friar, Jacques Clément, in August 1589. This latest cycle of religious and political assassinations left Henry of Navarre as King Henri IV of France at the end of the play, although in real-life it would take another four years and the new King's conversion to Catholicism before he could be crowned, a dramatic twist that even Marlowe probably would not have foreseen!

The events dramatised mean that Marlowe must have started writing the play at some time after the murder of Henri III in 1589, and finished it before it is recorded in Henslowe's Diary as being performed by "my lord stranges mene" on 30 January 1593. That entry is labelled "ne-" which may indicate a first performance.34 Extensive analysis by 35 has shown that Marlowe used as his primary source for the St Bartholomew's Day scenes an English translation of A True and Plaine Report of the Furious Outrages of Fraunce, attributed on the title page to the pseudonymous and published just a year after the massacre.36 In another article Kocher identifies a range of contemporary pamphlets that offer up material that could have been used by Marlowe for the subsequent scenes covering the reign of Henri III.37 However, that the subject-matter is so recent means that Marlowe may have had access to people with direct experience of the events he was dramatising, and the silent appearance of an "English Agent" in the climatic death-bed scene of Henri III raises a tantalising (although highly unlikely) possibility of some more direct involvement.

Hero & Leander

The partially completed poem of Hero and Leander is undoubtedly Marlowe's most beautiful verse,38 an erotically charged adaptation of the Greek myth about the two lovers separated by the Hellespont waterway. The story was much loved by Elizabethans, and inspiration was available to Marlowe via epistles XVIII and XIX of 's Heroides and translations of the sixth century retelling by the pseudonymous ,39 but this poetry is all very much Marlowe's original work. In Abydos lived "amorous Leander, beautifull and yoong" with "dangling tresses". He falls for the "louely faire ... Hero, Venus nun", who alas lived across the sea in Sestos. She has taken a vow of chastity but, unperturbed, Leander offers to swim across the Hellespont every night if they can be lovers and she cautiously agrees, offering to light a lamp in her tower to guide him. The Greek legend ends tragically with Leander setting out one stormy night only for the wind to blow out Hero's lamp, thus causing him to lose his way and drown. Distraught at seeing his body wash up on the coast, Hero throws herself from the tower and dies beside him.

In a little over 800 lines of rhyming heroic couplets, Marlowe sublimely captures the nervous sexual tension and consensual loss of virginity with not a little wit and humour, whilst vividly portraying some fine detail. Despite the heterosexual subject matter, the poet adds an undercurrent of the homoerotic when Neptune mistakes the swimming Leander for Ganymede, and in the description of Leander's body "straight as Circes wand, Joue might have sipt our Nectar from his hand", such that "some swore he was a maid in mans attire, for in his lookes were all that men desire...". Marlowe's verse ends after the couple's first night together, Hero's virginity left not like "jewels [which] being lost are found againe, this neuer, 'tis lost but once, and once lost, lost for euer".

It seems unthinkable that Marlowe did not intend to complete this sublime verse tale, his premature death at Deptford the most likely interruption. He was perhaps working on it at Scadbury near Chislehurst in the spring of 1593 where he had likely gone to escape the plague, and mentioned as a likely location for Marlowe in the warrant for his arrest issued on 18 May 1593.40 His host at Scadbury, Thomas Walsingham, was dedicatee of the first printing of Marlowe's poem, and his wife Audrey dedicatee to its second.41 The poem was first licensed to John Wolf four months after the events in Deptford,42 but it was Edward Blount who first published Marlowe's verse alone in 1598. At around the same time as this first edition, Blount transferred his registration to Paul Linley enabling the latter to publish in that same year Marlowe's verse together with the poem's posthumous completion by George Chapman.43 Chapman it was who divided Marlowe's verse into two "sestiads",44 adding four of his own and prefacing all six with introductory "arguments". His additions are worthy but somewhat dull compared to Marlowe's sparkling and teasing roller-coaster of emotion, but still far better than Henry Petowe's attempt at completion also published that same year.45

Ovid's Elegies

Amores ("The Loves") was 's first completed volume of poetry, published in 16 BC when the Roman poet was aged about 27, and made up of five individual books of elegies. He later edited it down to three books, producing the version that has survived and which Marlowe translated comprising 48 elegies. Written in the first person and using elegiac couplets, the Amores recounts a Roman student's infatuated affair with a married woman, the beautiful Corinna of higher class whom he initially seduces. The author is selfish, mean-spirited and full of complaints, displaying jealousy towards Corinna's husband and other lovers, and does not appear to enjoy many of their sexual liaisons.

The result of Marlowe's work is uneven in poetic quality, and contains some fairly basic errors in his Latin translation of . It is therefore generally considered most likely to have been written whilst he was a student at Cambridge. It was published in a number of forms after Marlowe's death. Two editions before 1599 entitled Certaine of Ovids Elegies each comprised the same selection of just ten of the most licentious elegies. Two others containing All Ovids Elegies are also undated but "appear to date from the close of the sixteenth century".46 All these editions claim to have been printed overseas "at Middlebourgh" in the low countries, likely trying to put a surreptitious publication beyond the reach of English censors (there is no record in the Stationers' Register of course). All these editions had Marlowe's Elegies bound with the satirical Epigrammes of , and it was perhaps that collection even more than the salacious elegies that caused the combined publication to be included on a list of books to be banned and burned by the Bishops in June 1599.47

The First Book of Lucan

The Roman poet Lucan's dark epic poem De Bello Civili (On the Civil War), popularly referred to as the Pharsalia, recounts the battle for Rome between Julius Caesar and the Republican Roman senate led by Pompey around 48 BC. In particular, it describes the Battle of Pharsalus, a town in Thessaly, Greece, in which Caesar decisively defeated Pompey before going on to turn the Republic into the Empire. Lucan (AD 39-65) began writing his poem in AD 61 over a century after the battle when he was good friends with the current emperor Nero (r.AD 54-68). But the pair fell out as Lucan became critical of the increasingly despotic emperor, and Nero banned publication of his work. Lucan continued writing his epic, but became involved in the failed Pisonian conspiracy of AD 65 and was compelled to commit suicide along with his dramatist uncle, Seneca. At the time of his death aged just 27, Lucan had completed nine books and part of a tenth book of a planned twelve.

Marlowe translated the first book of Lucan's Pharsalia (just shy of 700 lines) which introduces the conflict and recounts the initial actions, including Caesar crossing the Rubicon river. Lucan detested Caesar but was also critical of Pompey, Marlowe's memorable translated lines summing up this pair that "always scorn'd second place: Pompey could bide no equall, nor Caesar no superior" [l.125-6]. The cataclysmic chaos of Lucan's world-view may have appealed to a young Marlowe, and Lucan's famous line that "all great things crush themselues" [l.81] certainly has a Marlovian air. His translation is one of the earliest English poems to use blank verse, likely anticipating Tamburlaine, and the result is more impressive than the Elegies.48 But it again exhibits regular Latin translation errors, and is thus generally also considered most likely an early student effort. As with Marlowe's other poetry it was printed some years after his death in a single quarto edition of 1600, containing an unorthodox dedication by Thomas Thorpe to fellow publisher Edward Blount "in the memory of that pure Elementall wit Chr. Marlow: whost ghoast or Genius is to be seene walke the Churchyard in (at the least) three or foure sheets".49

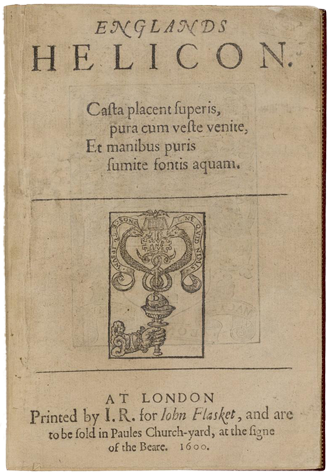

Other Verse: the Shepherd, the Judge and the Countess

Perhaps the best-known verse attributed to Marlowe is the short pastoral poem The Passionate Shepherd to his Love, which posthumously appeared in various forms in different printed publications. The longest and perhaps most authoritative is the six-stanza version credited to "Chr. Marlow" that appears in England's Helicon,50 an anthology of poetry published in 1600 by John Flasket (who also published an edition of Hero & Leander that same year).51 The first-person verse has the passionate shepherd inviting a shepherdess to "come liue with mee, and be my loue" and enjoy a perfect rustic life full of all the material delights that such a pastoral idyll has to offer, made from roses, poesies, flowers, myrtle, lamb's wool, straw, ivy buds along with buckle and studs of gold, coral and amber. Flaskett also prints the shepherdess' riposte (by "ignoto" i.e. unknown, but subsequently attributed to Sir Walter Ralegh)52 rejecting the offer of these "pretty pleasures" since they, like love, will likely wither with age: "But could youth last, and loue still breede, Had ioyes no date, nor age no neede, Then these delights my minde might moue, To liue with thee, and be thy loue". It is not clear when Marlowe wrote The Passionate Shepherd, but likely before The Jew of Malta (1589-90) which parodies this verse in the scene in which Ithamore suggests he and Bellamira should elope to Greece once they have the blackmail money from Barabas.53

In addition to this, two further small pieces of writing are worthy of mention, generally attributed to Marlowe by dint of his association with the people involved. The first is a twelve-line eulogy in Latin hexameter for Sir Roger Manwood who died on 14 December 1592 aged about 67.54 Manwood had been Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer since 1578, a position that also gave him a position in the Court of the Star Chamber, and he was involved in many of the big Elizabethan legal cases over the next 15 years. Manwood had also been one of a number of judges who sat on the bench at the Old Bailey trial of Marlowe and his friend Thomas Watson on 03 December 1589, to hear the case of the Hog Lane affray that claimed the life of William Bradley some three months earlier. As Marlowe was acquitted and Watson found to have killed Bradley in self-defence, Marlowe may well have had reason to write a grateful eulogy for the judge, who also happened to live in the Hackington parish near Canterbury. Manwood's career had been tarnished at the end by accusations of bribery, and it is difficult to disentangle from the ambiguous Latin whether the eulogy is wholly in praise of this "terror of night-stalkers, flayer of prodigals, Jovian Hercules, raptor of robbers...".55

The second is not verse by Marlowe himself, but rather a dedicatory epistle prefacing the posthumous publication of his dead friend Thomas Watson's Latin epic Amintae Gaudia. Watson was buried on 26 September 1592 at the church of St. Bartholomew the Less in London. The book was entered in the Stationer's Register just over six weeks later,56 and it may be that Marlowe, if it was he, might have had some hand in seeing it into print. The epistle is dedicated "to the most illustrious woman, adorned with all the gifts of mind and body, ", and is signed "C.M.".57 It purports to be fulfilling the final wish of Watson, who "as he lay dying humbly beseeched you and committed to your care the safety of this child" (i.e. his book). Mary Sidney, brother of Philip, was very much a poet in her own right, would publish a wide range of work including her own translation of The Tragedie of Antonie, was married to Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke who was patron of Pembroke's Men, and was a very generous literary patron. C.M. is hopeful that he might earn some patronage of his own: "I, whose very slim ability is owed to the seashore myrtle of Venus and Daphne's always-greening hair, on the first and every page of these poems will beg your favour, chosen-lady of the Muses".58 Alas, if this was Marlowe, he would not be the recipient of any such favours from the countess, for he would be dead himself inside six months.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: The Prologue to Tamburlaine the Great Part I, line 5. Back to Text

- Note 2: The Prologue to Tamburlaine the Great Part II, lines 1-3. Back to Text

- Note 3: , Timber, or Discoveries Made Vpon Men and Matter (London 1641). Back to Text

- Note 4: This EEBO text is a publication, also 1598, containing the first two sestiads by Marlowe, but also the remainder of the poem finished by George Chapman. Edward Blount's publication contained only Marlowe's verse. Back to Text

- Note 5: None of the published editions of Marlowe's translation of Ovid's Elegies (some containing all the elegies, others just a selection) are dated; all were published probably surreptitiously and claim to have been done so in Middleburgh in Holland. But one edition at least must have been published by 01 June 1599 when a commandment from the Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift included "marlowes Elegyes" in a list of "unsemely Satyres & Epigrams" published without their approval that were to "bee presentlye broughte to the Bishop of London to be burnte" - (Ed.), A Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers, 1554–1640, 5 volumes (London, 1875–1894), III.677-78. Back to Text

- Note 6: , The English Myrror (London 1586) - see EEBO text. Back to Text

- Note 7: , The Foreste, or Collection of Histories No Lesse Profitable (London 1571) - see EEBO text. Back to Text

- Note 8: , Magni Tamerlanis Scytharum Imperatoris Vita (Florence, 1553). Back to Text

- Note 9: (Ed.), The Revels Plays: Tamburlaine (Manchester University Press, 1999) p.33 states "It has been convincingly demonstrated that it was Whetstone's version of Mexia that Marlowe used, not that of Thomas Fortescue", citing , Spanish Literary Influence on the English Drama to 1625 (doctoral thesis, University of Cambridge, 1967) pp.47-58 and , The Principal Source for Marlowe's Tamburlaine in Modern Language Notes Vol. 58.6 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1943) pp. 411–17. Back to Text

- Note 10: , Preface to Perimedes the Blacke-Smith (London, dated 29 March 1588). "Merlin" is quite possibly a play on common variants of Marlowe's surname. For example, at Cambridge University he is often referred to as (Christoferus) Marlen or Marlin in the Cambridge University records and Corpus Christi buttery book records - see [Honan] pp.78-88. Back to Text

- Note 11: A Libell, fixte vpon the French Church Wall, in London. Anno 1593o, a transcription of which was discovered in Bodleian Library, MS.Don.d.152 f.4v by and reproduced by him in Marlowe, Kyd, and the Dutch Church Libel, English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 3.1, Studies in Renaissance Drama (Winter 1973), pp. 44-52 JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43446737. Accessed 10 March 2025. Back to Text

- Note 12: (Ed.), Letters of Philip Gawdy of West Harling, Norfolk, and of London to various members of his family, 1579-1616 (London 1906): "Yow shall vnderstande of some accydentall newes heare in this towne thoughe my self no wyttnesse thereof, yet I may be bold to veryfye it for an assured trothe. My L. Admyrall his men and players having a devyse in ther playe to tye one of their fellowes to a poste and so to shoote him to deathe, having borrowed their Callyvers one of the players handes swerved his peece being charged with bullett missed the fellowe he aymed at and killed a chyld, and a woman great with chyld forthwith, and hurt an other man in the head very soore. How they will answere it I do not study vnlesse their profession were better, but in chrystyanity I am very sorry for the chaunce but God his iudgementes ar not to be sear[ched] nor enquired of at mannes handes. And yet I fynde by this an old proverbe veryfyed ther never comes more hurte then commes of fooling... xvj th of November 1587. " Back to Text

- Note 13: [Henslowe-Diary] pp.23-33. The first part of Tamburlaine is performed fifteen times in that period, starting on 28 August 1594 with a packed theatre and impressive receipts of £3 11s. Popularity of the first part dwindles a little, and Henslowe it seems decides in December to put both plays on together, Part II performed a night of two after Part I. This is repeated seven times, with the sequel generating bumper receipts of £3 2s on it's second showing on 01 January 1595, two days after Part I took just 22 shillings (30 December 1594). The final performances were on 12/13 November 1595, with the sequel (32s) again more popular than the original play (18s). Back to Text

- Note 14: "The Enventary tacken of all the properties for my Lord Admeralles men, the 10 of Marche 1598" includes an item "Tamberlyne brydell" [Henslowe-Diary] p.320. "The Enventorey of all the aparell of the Lord Admeralles men, taken the 13th of Marche 1598" includes "Tamburlynes cotte with coper lace" (p.321) and "Tamberlanes breches of crymson vellvet" (p.322). Although not extant, the inventories found in a bundle of loose papers in the Dulwich College collection were transcribed by Edmund Malone and published in 1790 before they disappeared. Back to Text

- Note 15: Historie of the Damnable Life, and Deserued Death of Doctor John Faustus ... translated into English by P.F. Gent (London 1592) - see Internet Archive digital copy, and the text of the 1618 edition at EEBO. The title page also stated this 1592 edition was "new imprinted and in conuenient places imperfect matter amended: according to the true Copie printed at Franckfort", suggesting that this was perhaps not the first edition of the English translation. The anonymous German original published by Johann Spies five years earlier which P.F. translated is Historia von D. Johann Fausten (Frankfurt am Main, 1587). For a summary of the evidence that Marlowe used the English translation and not the German original, see (Eds.), Doctor Faustus A- and B- Texts (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1993) pp.4-5. Back to Text

- Note 16: (Eds.), Doctor Faustus A- and B- Texts (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1993) pp.1-2. Back to Text

- Note 17: [Henslowe-Diary] pp.24-60. That makes Doctor Faustus one of the most performed plays during the period of Henslowe's records (1592-7). Back to Text

- Note 18: , Histrio-mastix The players scourge, or, actors tragædie, divided into two parts (London 1633) - see EEBO text: "Nor yet to recite the sudden fearefull burning even to the ground, both of the Globe and Fortune Play-houses, no man perceiving how these fires came: together with the visible apparition of the Devill on the Stage at the Belsavage Play-house, in Queene Elizabeths dayes, (to the great amazement both of the Actors and Spectators) whiles they were there prophanely playing the History of Faustus (the truth of which I have heard from many now alive, who well remember it) there being some distracted with that fearefull sight;". Prynne was a puritan polemicist and was using this recollected event to denounce public playing. The Belsavage Inn off Ludgate Hill near St.Pauls was one of four London inns used as playhouses in this period, and had an outdoor stage in the courtyard. The Privy Council banned all use of the city inns for playing in 1594, so any production of Doctor Faustus there must have been before that. Back to Text

- Note 19: See for example (Eds.), Doctor Faustus A- and B- Texts (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press, 1993) pp.70-2. Bevington and Rasmussen suggest "a possible candidate not heretofore proposed is Henry Porter, Marlowe's contemporary at Cambridge and a dramatist for the Admiral's Men at the time Marlowe was writing Tamburlaine and Doctor Faustus, whose repeated use of the phrase 'Do you hear?' in The Two Angry Women of Abingdon c.1587-8 ... is liberally sprinked in the A-text of Doctor Faustus." More extensive digital textual analysis in 2025 by Dr Darren Freebury-Jones provided strong evidence for Porter's involvement. Henslowe paid for additions to the play over a decade later, recording a £4 payment to Samuel Rowley and William Bird on 22 November 1602. Back to Text

- Note 20: [Henslowe-Diary] pp.16-47. That is five more than the second most frequent play, The Wise Man of West Chester, which recorded thirty-one performances. Of the first thirteen recorded performances of The Jew of Malta whilst Marlowe was still alive in the year to February 1593, eight produced receipts of over £2 whilst the lowest takings were 33s. Back to Text

- Note 21: The quote is from prosecutor Sir Thomas Egerton. The trial took place on 28 February 1594 where Dr Roderigo Lopes and two others were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. Queen Elizabeth delayed for three months before signing the death warrant of her physician, and Lopes was only executed on 07 June 1594. Henslowe records eight performances of The Jew of Malta between 03 April and 10 July 1594, including four during June (although takings are not that high). It is also at this period on 17 May 1594 that Nicholas Ling and Thomas Millington paid their sixpence to have the play entered in the Stationers Register [SRO3612] although there is no known publication of the play by them. There is also an entry the previous day on 16 May 1594 for the publisher John Danter registering "a ballad intituled the murtherous life and terrible death of the riche Jew of Malta". Back to Text

- Note 22: [Henslowe-Diary] p.321, in "The Enventary tacken of all the properties for my Lord Admeralles men, the 10 of Marche 1598" is an item "j cauderm of the Jewe" [one cauldron]. The following two expenses are listed in [Henslowe-Diary] p.170: "Lent vnto Robart shawe & mr Jube the 19 of maye 1601 to bye divers thing[s] for the Jewe of malta the some of ... vli" [£ 5], and the next entry:"lent mor to the littell tayller the same daye for more thing[s] for the Jewe of malta some of ... xs" [10 shillings].Back to Text

- Note 23: Heywood says in his Epistle Dedicatory in the 1633 Quarto that the play is "now being newly brought to the Presse" which may imply previous edition(s). As noted above, there is an entry for the play in the Stationers' Register for Nicholas Ling and Thomas Millington [SRO3612] dated 17 May 1594, but no record of any publication by them survives. Back to Text

- Note 24: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.232. Back to Text

- Note 25: (Ed.), The Jew of Malta (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press 1997) p.17. Back to Text

- Note 26: (Ed.), The Jew of Malta (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press 1997) pp.5-7. Back to Text

- Note 27: , The Schoole of Abuse conteining a plesaunt inuectiue against poets, pipers, plaiers, iesters, and such like caterpillers of a comonwelth (London 1579) - see EEBO text: "And as some of the Players are farre from abuse: so some of their Playes are without rebuke: which are as easily remembred as quickly reckoned. The twoo prose Bookes plaied at the Belsauage, where you shall finde neuer a woorde without wit, neuer a line without pith, neuer a letter placed in vaine. The Iew & Ptolome, showne at the Bull, the one representing the greedinesse of worldly chusers, and bloody mindes of Usurers: The other very liuely discrybing howe seditious estates, with their owne deuises, false friendes, with their owne swoordes, & rebellious cōmons in their owne snares are ouerthrowne..." Back to Text

- Note 28: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.307 & p.308. Back to Text

- Note 29: et al, The Chronicles Of England, Scotland and Ireland (2nd Edition, London, 1587) Volume III - see [EEBO text]. Marlowe looks to have used the second 1587 edition much augmented by rather than the first 1577 edition, as per Edward the Second (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press 1994) pp.41-3, who also analyses at length Marlowe's adaptation of Holinshed pp.41-62. Fleming later became a curate at St Nicholas's Church in Deptford, assisting Reverend Thomas Macander at the time Marlowe was buried there on 01 June 1593. Back to Text

- Note 30: For example, Marlowe used the Scottish 'jig' in scene [II.ii] mentioned by in The Chroncle of Fabyan ... to thende of Queen Mary (London 1559), Volume II (a volume of Fabyan's Chronicle was to be found in the King's School library when Marlowe was a pupil there), and Edward being shaved in a puddle is described by in The Chronicles of England from Brute unto this present yeare (London, 1580). Back to Text

- Note 31: states "there is no mention of Pembroke's before 1592," when they were performing at Leicester for the last three months of the year, "and no reason to suppose it had an earlier existence" - [Chambers-ElizStage] Vol II p.128. The London theatres were closed from June 1592 after a riot by apprentices in Southwark, and then by a major outbreak of plague which followed in August and lasted until the spring of 1594. The theatres re-opened briefly in late December 1592 and through January 1593, and indeed Pembroke's Men are recorded as playing at court on 26 December 1592 and 06 January 1593 - [Chambers-ElizStage] Vol IV p.107. The play(s) performed at court are not recorded, but almost certainly wouldn't have been Edward the Second given some of the content! Pembroke's Men were on tour in the provinces in 1593 as a result of the plague, and Henslowe mentions they are in financial difficulty in a letter to Alleyn on 28 September 1593, which may explain the sale of playbooks to be printed. There is no record of the company performing in 1594, but it is possible they performed Edward the Second after the London theatres reopened in May and before William Jones published the play, although that gives us no futher help dating the play. Back to Text

- Note 32: Edward the Second (The Revels Plays, Manchester University Press 1994) pp.15-6. Forker speculates that two plays verbally indebted to Marlowe's play, Arden of Faversham and Soliman and Perseda, were possibly written by in which case such borrowings might have occurred when Marlowe and Kyd shared a lodging some in the middle of 1591. Back to Text

- Note 33: Only one copy held in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich was known to have survived after a second copy was destroyed in World War II. But recently a further copy was discovered in Germany by Jeffrey Masten in 2012. Back to Text

- Note 34: [Henslowe-Diary] p.20: "ne- Rd at the tragedey of the gvyes 30 [January 1593] . . . iij li xiiij s" A further ten performances are recorded by Henslowe during the period from June to September in 1594. Back to Text

- Note 35: [Kocher-Hotman]. Back to Text

- Note 36: [Varamund]. The real author is almost certainly François Hotman (1524-90). Back to Text

- Note 37: [Kocher-Pamphlets]. Back to Text

- Note 38: "The eight hundred lines written by Marlowe show a lucidity and an artistic mastery of detail, both in structure and in expression, which no other narrative poem in English literature can equal. We see here Marlowe's genius at its very best ... It is doubtful whether the English heroic couplet ... has ever been used with more perfect melody or more wonderful understanding of its peculiar capabilities" - [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.487. "Marlowe's genius is to use delicious poetry to narrate the tragic event of lost virginity, and then to present his verse as a new form of literature within the Ovidian poet's oscillating career. Hero & Leander is an erotic counter-epic of empire" - [Cheney-Striar] p.17. Back to Text

- Note 39: Although post-dating Marlowe, see for example this EEBO text of a translation appropriately by , The divine poem of Musæus. First of all bookes. Translated according to the originall, by Geo: Chapman (London 1616). Back to Text

- Note 40: "One of the messengers of her Majesties Chamber" was dispatched by the Privy Council with a warrant "to repaire to the house of Mr Thomas Walsingham in Kent, or to anie other place where he shall vnderstand Christofer Marlow to be remayning, and by vertue hereof to apprehend and bring him to the Court in his Companie. And in case of need to require ayd" - Acts of the Privy Council 24, p.244. Back to Text

- Note 41: Publisher Edward Blount's dedication to (the by then knighted) Sir Thomas Walsingham in his first edition of Hero & Leander (London, 1598) containing only Marlowe's verse refers to "the dutie wee owe to our friend, when wee haue brought the breathlesse bodie to the earth... yet the impression of the man, that hath beene deare vnto vs, liuing an afterlife in our memory, there putteth vs in mind of farther obsequies due vnto the deceased... I suppose my selfe executor to the vnhappily deceased author of this Poem, vpon whom knowing that in his life time you bestowed many kind fauors, entertaining the parts of reckoning and woorth which you found in him, with good countenance and liberall affection: I cannot but see so far into the will of him dead, that whatsoeuer issue of his brain should chance to come abroad, that the first breath it should take might be the gentle aire of your liking". George Chapman addresses the dedication of his continuation in Paul Linley's second edition (also London, 1598) to Lady Walsingham, confessing he is "being drawne by strange instigation to employ some of my serious time in so trifeling a subiect, which yet made the first Author, diuine Musæus, eternall." Back to Text

- Note 42: Entered in the Stationers' Register on 28 September 1593 for "a booke intituled Hero and Leander beinge an amorous poem devised by Christopher Marlow" to John Wolfe [SRO3514]. There is no record of any formal transfer of the publishing rights from Wolf to Blount. Back to Text

- Note 43: Blount transferred his licence for Marlowe's Hero & Leander to Linley on 02 March 1598 as recorded in an entry in the Stationers' Register [SRO4045]. That this was officially 02 March 1597 old style creates a slightly awkward chronology as both Blount's first edition and Linley's are dated 1598 on the title page. [Tucker-Brooke-Works] (p.485) speculates that Blount and Linley may have had an agreement of some sort, and notes that Blount was later involved in the 1609 and 1613 publications. Linley transferred all his titles to John Flasket on 26 June 1600 [SRO4322], including Hero & Leander which Flasket published in 1600 and 1606. All these editions after Blount's first contained both Marlowe's and Chapman's verse. Back to Text

- Note 44: The term "sestiad" seems to have been invented here by Chapman, he having divided the completed poem into six parts. The term may also hint at Sestos, the city where Hero lived. Back to Text

- Note 45: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.487: "This continuation, which is of no poetic value, was the work of a feeble young poet" Back to Text

- Note 46: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.553. Back to Text

- Note 47: Archbishop of Canterbury John Whitgift and Bishop of London Richard Bancroft commanded that a specific list of "unsemely Satyres & Epigrams" published without their approval "bee presentlye broughte to the Bishop of London to be burnte", a list which included "Davyes Epigrams, with marlowes Elegyes" - (Ed.), A Transcript of the Registers of the Company of Stationers, 1554–1640, 5 volumes (London, 1875–1894), III.677-78. These "commaundements" were issued by Whitgift from Croydon Palace on 01 June 1599. Back to Text

- Note 48: [Tucker-Brooke-Works] p.643: "It displays greater maturity than the Elegies, both in expression and in metrical skill." Back to Text

- Note 49: Thorpe is alluding to the sheets of Marlowe's publications on the bookstalls of St. Paul's Churchyard with a play on the winding sheet that the dead Marlowe would have been wrapped in. "A booke intituled Lucans firste booke of the famous Civill warr betuixt Pompey and Cesar Englished by Christopher Marlow" was originally registered to John Wolfe [SRO3513] on 28 September 1593, the same day as Hero & Leander [SRO3514]. Thorpe in his dedication refer's to Blount's "old right in it", but there is no record of Wolf transferring the rights of either poem to Blount. Both titles appear to have belonged to Paul Linley by the end of the decade, as "Hero and Leander with the. j. booke of Lucan by Marlowe" were transferred with all his other titles to John Flasket on 26 June 1600 [SRO4322]. Curiously the title page of Flasket's 1600 publication of Hero & Leander advertised the inclusion of the Lucan translation, but it was not present. There is no record of any transfer of rights for The First Book of Lucan to Thomas Thorpe who we may assume now owned it from his dedication, which also refers to Blount's "old right in it". The title page of the 1600 Quarto states that Lucans First Booke is "to be sold by Walter Burre, at the Signe of the Flower de Luce in Paules Churchyard", Burre presumably acting only in the capacity of book-seller. Similarly Shake-speares Sonnets published by Thorpe in 1609 was printed "by G. Eld for T.T. and are to be solde by William Aspley". Back to Text

- Note 50: Englands Helicon (London 1600) published by John Flasket. The anthology's title alludes to Mount Helicon famous in Greek mythology for two springs sacred to the Muses. See the text from this 1600 edition for both The Passionate Sheepheard to his Loue and The Nimphs Reply to the Sheepheard at EEBO. Back to Text

- Note 51: Four stanzas from The Passionate Shepherd together with just the first from The Nymphs Reply appeared the previous year in the questionable anthology entitled The Passionate Pilgrim (London, 1599) printed by William Jaggard which contained 20 poems all purported to be written by (only five certainly were). Back to Text

- Note 52: , The Compleat Angler or, the Contemplative Man's Recreation (London, 1653) pp.63-4 - see EEBO text: "'twas a handsome Milk-maid, that had cast away all care, and sung like a Nightingale; her voice was good, and the Ditty fitted for it; 'twas that smooth Song which was made by Kit Marlow, now at least fifty years ago; and the Milk maids mother sung an answer to it, which was made by Sir Walter Raleigh in his yonger dayes." Back to Text

- Note 53: Lines 1807-1816, or Act IV.ii.94-104, of which last two lines are "Thou in those Groues, by Dis aboue, Shalt liue with me and be my loue." Back to Text

- Note 54: The eulogy was part of material related to Marlowe found in two common place books belonging to Henry Oxinden and dating from the early 1640's which now belong to the Folger Library and which are digitised on their website. See the digitisation of the Manwood Eulogy on p.42. Oxinden made some notes on Marlowe garnered "from Mr Ald.", who was Simon Aldrich born in Canterbury around 1580 and who attended Corpus Christi Cambridge from around 1593, in particular around Marlowe's reputation for atheism: see digitasation of notes from Mr Ald pp.54-55 together with transcript. Ref: A semi-diplomatic transcription of selections from the Miscellany of Henry Oxinden at the Folger Shakespeare Library, edited by Julie Bowman, Meaghan J. Brown, Paul Dingman, Megan Heffernan, Talya Housman, Katherine Lazo, Kristin B. Leaman, Victor Lenthe, Joseph D. Mansky, Catherine Medici-Thiemann, Sarah Powell, Raashi Rastogi, Dylan Ruediger, Margaret Simon, Nancy L. Simpson-Younger, Misha Teramura and Jonathan Woods. "Miscellany of Henry Oxinden, ca. 1642-1670 V.b.110," Folgerpedia Article, Folger Shakespeare Library [Accessed 31 March 2025] Back to Text

- Note 55: English translation from [Cheney-Striar] pp.289-90. Back to Text

- Note 56: Entered in the Stationers Register on 10 November 1592 for "Master Ponsonby" [SRO3427]. William Ponsonby also published works by , and . Back to Text

- Note 57: There is at least one other example of a work similarly attributed not being by Marlowe. A manuscript thought lost containing an eclogue and sixteen sonnets and signed "Ch.M." and thus perhaps by Marlowe was re-discovered in 1986 and determined most likely to rather have been written by , a contemporary at Trinity College, Cambridge - see , Marlowe, Madrigals, and a New Elizabethan Poet (The Review of English Studies, OUP, Vol. 39, No. 154 pp. 199-216, May 1988) - [https://doi.org/10.1093/res/XXXIX.154.199]. Back to Text

- Note 58: English translations from [Cheney-Striar] pp.292. There is also an online Latin text version of , Amintae Gaudia (London, 1592) together with an English translation, edited by . Back to Text