Dido Queen of Carthage

A Critical History

Early Dismissal

Could it be possible that a certain was one of the earliest theatre critics to pass judgement on Dido Queen of Carthage?! Alas, probably not, for the rememberances in Hamlet of a play that involved "Æneas' tale to Dido ... of Priam's slaughter" do not bear much resemblance to Marlowe's drama. If Shakespeare had any memory of the play at all, few others did for the next two centuries. As with the staging, Dido Queen of Carthage and The Massacre at Paris have received the least amount of critical consideration of all the plays in the Marlowe canon. As mentioned in the textual history of the play, it was not until the beginning of the nineteenth century that the Romantic poets began to revive an interest in Marlowe, and not until 1825 that a text of Dido was re-published once more by Hurst in a collection of Old English Drama.1

For a long time, the play has not been particularly highly regarded. Some critics incorrectly dismissed it as largely a work of translation. described it as a "burlesque on Dido's story as treated by Vergil", and thought it "pretty quaint and painful".2 Others heavily criticised some of the weaker elements of dramatisation, in particular the triple suicide at the end, which many saw as a comedic anti-climax rather than a tragic climax ( described some elements of the play as "ridiculous").

A Little More Love

Twentieth century critics have shown themselves a little more sympathetic, perhaps taking their lead from no less a poet and critic than , who described the play as "underrated" and found some merit in what he viewed as an otherwise workmanlike dramatisation. "Dido appears to be a hurried play, perhaps done to order with the Aeneid in front of him. But even here there is progress. The account of the sack of Troy is in this newer style of Marlowe's, this style which secures its emphasis by always hesitating on the edge of caricature at the right moment".3

Some were still unmoved. The Marlowe scholar thought that Dido was "in itself of no more interest to modern readers than The Massacre at Paris",4 before dismissing it as "nothing but a rewriting of the first part of Virgil's Aeneid".5 Other commentators took the time to examine how Marlowe had significantly improved upon his source in many places, rather than simply performing a translation. cites the vivid and poetic description of the Grecians emerging from the wooden horse ("from out his entrails ... stern faces shin'd the quenchless fire ..." [II.i.182-7]) as a significant improvement on dry description of the Greeks sliding down a rope.6

, whilst recognising the deficiencies, still finds plenty to admire in much of the play. Amongst other things, Dido "contains some of the most human and humane of Marlowe's writing",7 whilst Aeneas' narrative describing the fall of Troy "is the most finely sustained speech in Marlowe".8 Writing at the time of Marlowe's quartercentenary in 1964, Steane was of the view that "Dido has remained largely where it was, read infrequently and little esteemed. This is a pity, for Marlowe put much of the best of himself into it". He wrongly predicted that the play "has weaknesses enough to prevent a successful stage revival, and there are limitations in the enthusiasms and sympathies, the qualities of mind. But the energy and fire shine out brilliantly, in a more admirable way than in Tamburlaine and without the destructive bitterness of the other works".9

But Steane too found the ending flawed. "The play, for all its fine and interesting qualities, is not a successful tragedy".10 Whilst not believing generally that the comedy in the play was detrimental to the ultimate sense of tragedy, Steane did think that the lack of gravitas displayed by the Gods had an impact. "Only an exceptionally fine fifth act could have made successful tragedy with these things working against instead of preparing for it. The last act of Dido is, in fact its greatest weakness, and the last scene quite fatal" (i.e. "the rapid succession of suicides").11 For all that, Steane remained an admirer: "the reading of Dido can still, however, be a great pleasure, and the weak fifth act by no means justifies the critical neglect of the whole play".12

In the first Revels edition of the play published in 1968, editor also finds much to admire in the play, whilst opining that the novice playwright had plenty still to learn. "In Dido, there is also fine narrative, in the long account of the fall of Troy; there are other kinds of fine poetic rhetoric; there may even be a 'melody such as English poetry had never achieved hitherto save in The Faerie Queene'; but there is as yet insufficient integration of words, melody and dramatic action".13

Much of the criticism prior to the last decade of the twentieth century concentrated on Marlowe's interpretation of the relationship between Gods and mortals compared to that he inherited from Virgil, and the resulting conflicts between love and duty. argued that Marlowe's play significantly transfigures his primary source rather than just imitating Virgil. For her, "the pursuit of love is incompatible with the demands of duty for both Dido and Aeneas (though he deserts her for the more 'Elizabethan reasons' of fame and honor rather than for any 'sacred mission)".14. Oliver notes that "Marlowe is much less sympathetic to the behests of the Gods" of which both Dido and Aeneas are a victim. "There is no suggestion that Dido is not to be pitied as the one who pays the price" (for Jupiter's insistence on the continuation of the mission to found Rome) whilst "a better man than Aeneas might not have been so weak as to let her pay it".15

Staged Improvement

With the play much more frequently performed since 1991, including a number of major US and UK productions in the new millennium, critics have been able for the first time able to draw on a range of staged interpretations by different directors to perhaps better see the potential of Dido Queen of Carthage in performance. At this time too, "approaches to Dido have reflected general changes in critical fashion. Since the late 1980s, Dido's role as woman and queen have been reassessed from the standpoints of gender, politics and history", as notes before proceeding to provide a comprehensive summary of recent criticism in these contexts, as well as that of race.16

Modern critics have seen Dido both as "faced with a 'male' decision between love and duty"17 and "in control, Aeneas one of her sights of power".18 observes that Dido "was not the only Chapel Royal play to present women as powerful authority figures... Playing with gendered expectations looks like a regular feature of the drama of both boy companies in the 1580s", but at the same time in the context of "tragic heroism, ... Dido was an exception in the overtly masculine world of late 1580s tragedy".19 concurs, identifying Marlowe's play as having "three claims to be revolutionary in the 1580s context: the central character [female], the use of blank verse, and the absence of moral commentary".20 Perhaps inevitably Dido is frequently compared to Queen Elizabeth I, the parallel invited by the contemporary 'Sieve Portrait' of the English monarch with Dido and Aeneas prominent in the background.

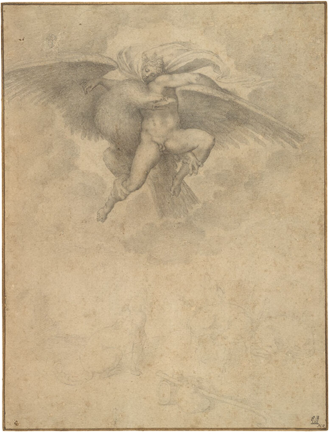

Marlowe's addition of the initial scene with Jupiter "dandling" Ganymede on his knee with its undercurrent of homosexuality has increasingly been applauded as transgressive by recent critics "if only for the message it sends",21 rather than being brushed under the carpet. cites "Jupiter's excessive homosexual desire as both inversion (of traditional norms) and subversion (the play ostensibly upholds the stereotypes of male reason and female passion)".22 interprets the scene as indicating that "male desire is more about power over others than rationality".23 notes that "Marlowe's audience knew about Jupiter's rape of Ganymede from Book Ten of Ovid's Metamorphoses. For Renaissance humanists, this was the definitive myth about homoerotic love. The abduction became an allegory of the soul's ascent to divine knowledge: Jupiter was the quintessential teacher, his cupbearer Ganymede the perfect pupil. This idealisation of boy-love subliminated, but could never completely efface, the carnal thrust of Jove's love for Ganymede".24

The subject matter, characters and setting of the play thus allow for modern analysis from a wide range of standpoints, but as concludes, Dido Queen of Carthage "is resistant to tidy critical analysis. It has been categorised as tragedy and satire and farce - and as pedestrian translation... The typical study has viewed Dido as exemplary fiction ... but rarely as a play written for performance [with] commentary on the performance possibilities ... mostly limited to the topics of children's learning and performance" (albeit with some notable exceptions such as the Eoin Price chapter quoted from above).25 Despite all this, perhaps nicely captures the simple essence that "what is really distinguished in Dido is the exquisite beauty of its verse as well the varying registers of its styles. The drama has the aspect of a poem, even of a courtly jeu d'esprit, but it is free from heaviness".26

Footnotes:

- Note 1: [Hurst-Robinson] Vol. II. Back to Text

- Note 2: [Revels-Oliver] p.ix. Trollope recorded his criticism in notes at the end of each play in his 1850 edition of [Dyce]. Back to Text

- Note 3: , The Sacred Wood - Essays On Poetry And Criticism (Methuen London, 1920), in the essay Some Notes on the Blank Verse of Christopher Marlowe. The essay is also reproduced in [Leech-Essays] pp.12-17. Back to Text

- Note 4: [Bakeless-Marlowe] p.255. Back to Text

- Note 5: [Bakeless-Marlowe] p.257. Back to Text

- Note 6: , essay Marlowe's Light Reading in Elizabethan and Jacobean Studies Presented to Frank Percy Wilson on his Seventieth Birthday (Ed. H. Davis & H. Gardner, Oxford Clarendon Press 1959) pp.28-9. Back to Text

- Note 7: [Steane] pp.42-3. Back to Text

- Note 8: [Steane] p.53. Back to Text

- Note 9: [Steane] p.29. Back to Text

- Note 10: [Steane] p.46. Back to Text

- Note 11: [Steane] p.48. Back to Text

- Note 12: [Steane] p.50. Back to Text

- Note 13: [Revels-Oliver] p.xlvii. Back to Text

- Note 14: ('Love Kindling Fire': A Study of Christopher Marlowe's The Tragedy of Dido Queen of Carthage (Institut fur Englishe Sprache und Literatur, Salzburg, 1977) cited in [Revels-Lunney] p.45. Back to Text

- Note 15: [Revels-Oliver] p.xlv. Back to Text

- Note 16: [Revels-Lunney] p.46-9. Back to Text

- Note 17: , Women in Power in Early Modern Drama (University of Illinois Press, 1992). Back to Text

- Note 18: , Marlowe's Politic Women pp.164-176 in Constructing Christopher Marlowe (Ed. J.A. Downie & J.T. Purnell, Cambridge University Press, 2000). Back to Text

- Note 19: , Marlowe in Miniature, chapter 3 in [Marlowe-Commerce] pp.53-4. Back to Text

- Note 20: [Revels-Lunney] pp.55-6. Back to Text

- Note 21: [Revels-Lunney] p.46. Back to Text

- Note 22: , Sex, Gender, and Desire in the Plays of Christopher Marlowe (Unversity of Delaware Press, 1997) p.91. Back to Text

- Note 23: , Marlowe and the Politics of Elizabethan Theatre (Harvester, Brighton, 1986) p.200. Back to Text

- Note 24: [Riggs] p.120. Back to Text

- Note 25: [Revels-Lunney] p.49. Back to Text

- Note 26: [Honan] p.102. Back to Text