Marlowe's Education

Grammar School

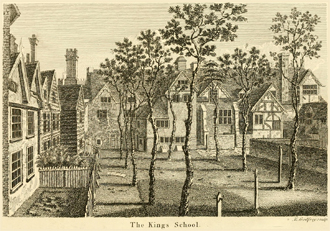

In addition to the improvement in educational opportunities during the early part of Elizabeth I's reign,1 Marlowe was probably still fortunate to be born in the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral with its long history of elite schools. Christopher received a grammar school education at the King's School which had been (re)founded less than forty years earlier following the dissolution of the Cathedral Priory. Records show Marlowe receiving payments as a King's Scholar at the school from the start of 1579, when he was only two months shy of his fifteenth birthday, until he left for Cambridge some two years later.

It seems likely that Canterbury had been an important educational centre since soon after St Augustine's arrival in 597. Sent by Pope Gregory, he established the monastery of Saints Paul & Peter (later renamed St. Augustine's Abbey) just outside the city. Educating young men was a vital part of the mission to spread Christianity throughout Britain, and future abbots and bishops received their early training at Canterbury, including Benedict Biscop who later founded the monasteries at Wearmouth and Jarrow in 674.2 Based at the latter just over half a century later, the Venerable Bede wrote in his history of a "golden-age" of ecclesiastical education in Canterbury around that time.3

A Benedictine priory was added to Canterbury Christ Church (Cathedral) by St Dunstan in the tenth century, the Archbishop spending his final years teaching in the Cathedral school there. But it was Archbishop Lanfranc who fully established a Benedictine monastic order at Christ Church Priory. Boys were educated and trained as monks for many centuries to come, with both entry criteria and discipline very strict. By the fourteenth century entrants had to demonstrate basic grammar, writing and singing and, if accepted, would be taught subjects including advanced grammar, logic and philosophy. Prospective young Canterbury monks would often go on to Oxford University to complete their education, such a well-worn path, in fact, that in 1361 a permanent hall called Canterbury College was established at Oxford to facilitate this process.

One of the earliest Almonry Schools was established by the Priory at Canterbury in 1320 for poor boys, although "no scholar shall be taken into the almonry unless he can read and sing in the chapel and is 10 years old."4 The school was located in the Almonry Yard5 at the north corner of the Cathedral Priory grounds with the city's Northgate just beyond, and the Aula Nova (New Hall) on the east side of this yard entered via the Norman Staircase. In quick time the school also had its own chapel built on the south side of the yard (1328). The Almonry had a dedicated schoolmaster by 1364 with a stipend paid by the Cathedral Priory (worth 6s 8d per annum by 1447-1511).6 A "Free Schoole" had also been founded elsewhere by the Archbishop for boys in Canterbury and existed before the end of the thirteenth century.7 The last headmaster of this Archbishop's School, John Twyne, would also be appointed head of the newly formed King's School.

The Canterbury Cathedral Priory of Christ Church was officially surrendered to King Henry VIII as part of the dissolution of the monasteries in March 1540. It was not long however before the Cathedral was newly constituted on 08 April 1541, the prior and monastic chapter replaced by a dean and twelve canons. The new foundation also made provision for a new school comprising fifty "King's scholars" of which it transpired nine were former novices and junior monks from the dissolved priory.8 The King's School building was initially located south of the Cathedral, but in 1559 it moved to the old priory buildings located in the Mint Yard (formerly Almonry Yard), with a Head Master (Twyne,9 paid £15 2s per annum) teaching the three upper classes, and a Lower Master (or "Under Master", the first being William Wells, receiving £6 5s 10d) teaching the lower three.

The cathedral statutes11 made provision at the new school that "there shall always be in our cathedral church of Canterbury, elected and nominated by the Dean … fifty boys, poor and destitute of the help of their friends, to be maintained out of the possessions of the church, and of native genius as far as may be and apt to learn: whom however we will shall not be admitted as poor boys of our church before they have learnt to read and write and are moderately learned in the first rudiments of grammar, in the judgment of the Dean or in his absence the Sub-dean and the Head Master. And we will that these boys shall be maintained at the expense of our church until they have obtained a moderate knowledge of Latin grammar and have learnt to speak and to write Latin. The period of four years shall be given to this, or … at most five years and not more".12

Pupils had to be at least nine years old to be admitted when a vacancy arose,13 and not yet past their fifteenth birthday (which Marlowe was fast approaching at the start of 1579). "No one shall be admitted into the school who cannot read readily, or does not know by heart in the vernacular the Lord's Prayer, the Angelic Salutation, the Apostles' Creed and the Ten Commandments". Further, any student "wholly ignorant of Grammar" could not start in the first class until he had learned the basics "as it were out of class".14

In 1571, a tragic event occurred close to the school that may have provided some gruesome distraction for the King's scholars from their daily grind of declension and translation. Cardinal de Châtillon, who had fled France three years earlier in fear of his life, died in suspicious circumstances whilst staying at a Cathedral lodging house15 adjacent to the school. The Cardinal was none other than Odet de Coligny, brother of Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France, the Huguenot leader whose assassination the following year would trigger the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre dramatised by Marlowe twenty years later. Earlier in life the Cardinal had been rewarded with many titles and benefices by the French Catholic church, and was a member of the King's Council under Henri II in the 1550s. But as the Wars of Religion erupted, he converted to Calvinism in 1561, and despite acting as an intermediary between the protestants and Catherine de Medici, he fled in haste and sought refuge in England in 1568 after learning of plans to seize him at his house.

By late 1570, his brother the Admiral had signed a treaty with Queen Catherine, and the Cardinal was hopeful of a return to France. He was also engaged in discussions with the French Ambassador in London on the subject of the proposed marriage of the then Duke of Anjou (future Henri III) to Elizabeth I, with whom the Cardinal had also found some favour. After a number of thwarted attempts to sail home, he left London again at the end of January 1571, lodging at Canterbury whilst likely en route to Dover. But his health was seen to be deteriorating slowly, and in early March he was reported as suffering from fits, and growing "weak and faint".16 On 24 March 157117 he lost the ability to speak and died at his Canterbury lodging later that evening at the age of 53. His wife claimed that the Cardinal had been gradually poisoned, citing the perforated stomach observed at his autopsy. The Queen ordered a Commission of Enquiry, in which damage to other organs was noted but no conclusive evidence of poisoning could be found.18 Intriguingly, two years later Odet's valet-de-chambre, a Basque called Vuillin, confessed to poisoning the Cardinal whilst in his service by means of a "perfumed apple". Vuillin had been captured at the protestant bastion of La Rochelle as a Catholic spy, and this confession on the gallows cannot perhaps be considered wholly reliable.19

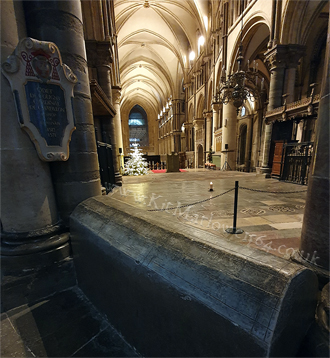

Marlowe was just seven years old when Odet de Coligny died in Canterbury, and would not yet be attending the King's School. He may anyway have been familiar with the Cardinal's death, perhaps inspiring an interest in the events dramatised in his play The Massacre at Paris. The Cardinal de Châtillon was buried in what was expected to be a temporary tomb at the east end of Canterbury Cathedral, pending the return of his body to France. But that never happened, and he remains buried in Canterbury to this day.

Plaque: "Odet de Coligny / Cardinal of Châtillon / Bishop of Beauvais / 1517 - 1571"

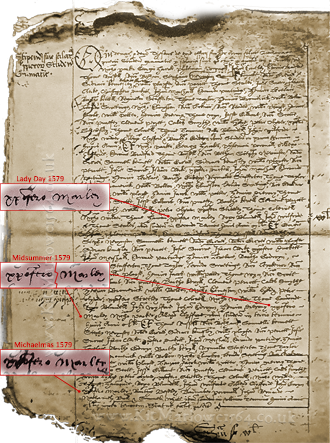

By the late 1570's, the King's Scholars received an allowance of £4 per annum to pay for gowns and commons (meals), which was paid quarterly. "Christopher Marley" was awarded a Queen's Scholarship soon after Christmas 1578,20 and received his first quarterly payment of £1 on Lady Day, 25 March 1579.21 The last payment to him is recorded at Michaelmas (September) 1580, when he was aged 16, and he had left for Cambridge by December. Marlowe we may surmise must have worked his way through the full "five or six ranks or classes" taught at the King's School in order to qualify for a place at university, and although the statutes allowed for four years of scholarship payments, it is just about feasible that an aspiring high-flyer could have moved through all six forms in two years. The Head Master was required to "diligently test the abilities of the scholars and ascertain their progress in learning," and "those he shall find to be fit and industrious he shall, at least three times a year, call up to the higher forms, namely from the first to the second, from the second to the third, and so on as each shall be thought fit".22 Another possibility, as Edwards suggests, is that his father's middling income was sufficient for Marlowe to have been a paying Commoner at the school prior to the award of his scholarship.23 There is also record that John Marlowe provided lodging and footwear for two other pupils at the school, and this may have been a factor in Christopher earning a place.

The student day was long and hard, starting at 6am with prayers, verses & responses, and psalms. Each day the Under Master would choose an English sentence for the students "to turn exactly into Latin, and to write it carefully in their parchment note-books". Marlowe would have begun his grammar education being taught the "rudiments of English, … and to turn a short phrase of English into Latin". In the next form, as well as more advanced grammar, the student would "learn a little higher" and "shall run through Cato's verses, Aesop's Fables, and some Familiar Colloquies". "In the Third Class", the last taught by the Under Master, Marlowe and his fellow pupils would have "Terence's Comedies, Mantuanus' Eclogues, and other things of that sort [made] thoroughly familiar to them".

Inscription: Remember CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE 1564-1593 Poet & Dramatist the Muse's [sic] darling / HERE STOOD THE BUILDING WHERE AS A KING'S SCHOLAR HE RECEIVED HIS EARLY EDUCATION.

From the fourth form onwards, students would be under the Head Master's tutelage. Marlowe would be expected to learn "the Latin syntax readily; and be practised in the stories of poets, and familiar letters of learned men, … commit to memory the Figures of Latin Oratory and … be practised in making verses and polishing themes" as well as "translating the chastest Poets and the best Historians". In the final (sixth) form, students would be instructed in Erasmus, "learn varyings of [Latin] speech in every mood", "taste Horace, Cicero and other authors of that class", whilst also "compet[ing] with one another in declamations so that they may leave well learned in the school of argument".24

Lessons during the day only ended at the stroke of five with the recitation of another psalm. Dinner and more versicles and responses followed, and then the younger boys were obliged to recite their lessons to the older pupils. The school day ended at 7pm, whereupon the non-boarders (of which Marlowe was presumably one) were allowed to depart for home.25

The extant school accounts that record Marlowe's scholarship payments also list the names of the other scholarship boys at school with Marlowe. William Urry's meticulous research has added a little biographical flesh to some of these bare names.27 One contemporary was William Lyllye, listed as a scholar at the King's School from at least Michaelmas 1578 onwards. William was a (much) younger brother of the writer and playwright John Lyly (c.1554-1606), who is also likely to have attended the school in the 1560s. Leonard Sweeting was eight months older than Marlowe, having also been baptised at St George's Church on 16 May 1563 by his father, the somewhat ill-qualified parish vicar, Reverend William Sweeting. Living just across the road from the church, Christopher likely already knew Leonard well, and even after the Reverend’s death in 1574, his poor family are seen living in St George’s Gate close by. Despite these difficulties, Leonard did well for himself, becoming a registrar and Notary Public. A church court document from 1608 contains a list of books belonging to Sweeting which included some poetry by his old school-mate: The Garden of Muses (a commonplace book by John Bodenham published in 1600 containing an anthology of nearly 4,500 short verse quotations, including many from Marlowe's Hero and Leander and Edward II) and a copy of Hero and Leander itself.

Unsurprisingly, many of the King's Scholars went on to an ecclesiastical career, although not always in the orthodox Church of England. Samuel Kennett was seven months older than Marlowe and left the King's School a few months before him (by Michaelmas 1580). He became a warder at the Tower of London where he was converted to Catholicism by the imprisoned priest John Hart. This conversion inspired Kennett to flee abroad to the seminary at Rheims (arriving 23 June 1582), where Marlowe was later accused of going. Kennett left Rheims for Rome over a year later (13 August 1583) and was finally ordained priest in 1589. He returned to Rheims two years later from where he was sent on a mission to England under the pseudonym William Carter.

At the other end of the spectrum, Henry Jacob (b.1563) became a Brownist and went into exile in Holland in 1593. After his return in 1616, he founded England’s first congregational church in Southwark, and later a settlement in Virginia (Jacobopolis). Meanwhile, William Potter, whose father was a butcher in nearby Iron Bar Lane, followed a more orthodox career in the English church, including a spell as curate at St Dunstan's-in-the-East in London from 1588. Benjamin Carrier, two years Marlowe's junior, was a King’s scholar by the time Marlowe left for Corpus Christi and followed him there as a sizar in 1582. He held a number of livings in Kent and was a Cathedral canon at Canterbury, but defected to Rome late in life on the pretext of visiting a spa for his health.

Despite some more enlightened views on teaching methods, it seems that the stick rather than the carrot was very much the default method of 'encouraging' such boys to learn in the Elizabethan classroom. Contemporary woodcuts commonly show school masters with a birch readily to hand (see for example the 1573 title page of Nowell's Catechism and the 1592 Elizabethan Schoolroom woodcut). The seven-year-old Simon Forman was beaten by his schoolmaster Willian Rydout at the Wilton free school "which made me more diligent to my book",29 whilst Nashe has his protagonist Will Summer declare "Nownes and Pronounes, I pronounce you as traitors to boyes buttockes".30

The educationalist Roger Ascham recounts dining with Lord Burleigh and others in 1563, and Master Secretary sharing news with him that "diuerse Scholers of E(a)ton, be runne awaie from the Schole, for feare of beating". It was Burleigh's "wishe that some more discretion were in many Scholemasters",31 a progressive view shared by Ascham, who wryly observed regarding the "making of latines" that "the scholer, is commonlie beat for the making, when the master were more worthie to be beat for the mending, or rather, marring of the same: the master many times, being as ignorant as the childe".32 As an edition of Ascham's book The Scholemaster was to be found in the King's School headmaster's library, we can perhaps hope that Marlowe enjoyed a more progressive educational environment with less beatings, and that his masters were not as ignorant as the children.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: "Children of the 1560s were, as a group, the most literate in English history to that time thanks to economic imperatives, humanistic enthusiasm for the value of education as a formative process, and Protestant enthusiasm for personal study of scripture" – , The Birth of the Elizabethan Age – England in the 1560's (Blackwell Oxford, 1993) p.170. Back to Text

- Note 2: , A History of the King’s School Canterbury (Faber & Faber, London, 1957) p.17. Back to Text

- Note 3: Theodore of Tarsus arrived in Canterbury to become Archbishop in 668, and along with Hadrian established a new school that introduced a wide and innovative curriculum deriving from the eclectic cultures the pair had experienced in Greece, Rome, Africa and Byzantium. The Venerable Bede recorded that "there daily flowed from them rivers of knowledge to water the hearts of their hearers; and, together with the books of holy writ, they also taught them the arts of ecclesiastical poetry, astronomy, and arithmetic. A testimony of which is, that there are still living at this day some of their scholars, who are as well versed in the Greek and Latin tongues as in their own, in which they were born." - , Historiam Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (An Ecclesiastical History of the English People) (Jarrow-Wearmouth c.731) Book IV Chapter 2, translation at https://www.heroofcamelot.com/docs/Bede-Ecclesiastical-History.pdf [Accessed 04 March 2023] Back to Text

- Note 4: Original Latin and translation in , Educational Charters and Documents 598 to 1909 (Cambridge University Press, 1911) p.xxxii. Back to Text

- Note 5: In Marlowe's day, this was named Mint Yard for a royal mint located here 1540-55, and was the centre of the King's School. See the excellent maps of the medieval Cathedral precincts and priory before and after the 1541 foundation produced by Canterbury Archaeological Trust (1984) [Accessed 12 March 2023] Back to Text

- Note 6: Edwards p.35. Back to Text

- Note 7: Edwards p.36-37. The schoolmaster witnesses a document in 1259. See also a document from 1291 granting powers to the headmaster of the Archbishop's School in Leach pp.232-3. Back to Text

- Note 8: Edwards p.61. Of the 52 monks belonging to the Cathedral Priory at the dissolution, 28 received posts as part of the new foundation. The last prior, Thomas Goldwell, retired with a pension. Back to Text

- Note 9: John Twyne would appear to have been an interesting character, who remained headmaster of the King's School for nigh on twenty years until 1561, and dying a further twenty years later when Marlowe was aged 17. Born in Hampshire c.1501, Twyne graduated from Oxford in 1525 and moved to Canterbury where he became "supreme Moderator of the [Archbishop's] free school within the cemitry gate at Canterbury". After becoming the first headmaster at the King's School in 1541, he also served as Sherriff, Alderman and Mayor of Canterbury, even enduring a short spell in the Tower of London in 1553 when as MP he offended the Duke of Northumberland. After a visitation to the King's School in 1560, Archbishop Parker ordered that "Mr Twine, their Schoolmaster shall not intermedle with anie publicke office of the incorporation of the Towne or Cittie of Canterberie, but holie with diligence to applie his Schole and Schollers, and that he should utterlie abstaine from riott and dronkynnes, upon paine to be removed from the said rome of Scholemaster or office of teachinge" - Leach p.471. By the following year the King's School had a new headmaster. In 1562 Twyne was accused by one Mrs Basden of being "a very conjuror" and of "filthy & unseemly talke". He was however a respected antiquary praised by both William Camden and Raphael Holinshed, his work on the early history of Britain, De Rebus Albionicis, Britannicis, atque Anglis Commentariorum, was written mostly whilst headmaster of the King's School but only published posthumously in 1590 by his son Thomas (1543-1613), some nine years after John Twyne had died on 28 November 1581, aged around eighty. Another of Twyne's three sons, Laurence (d.1988), translated and published The Patterne of Painfull Adventures (London, 1576), a prose novel of which a later reprint (1607) [Text] was a source for Shakespeare's Pericles, Prince of Tyre (London, 1609). For more on John Twyne, see Edwards pp.69-74, Wikipedia, and ODNB. Back to Text

- Note 10: William Gostling, A Walk In and About the City of Canterbury (Simmons & Kirkby, Canterbury, 1777). The engraving of All Saints Church (p.177) by Richard Godfrey appeared in the second edition of the book published in 1777 following Gostling's death. Back to Text

- Note 11: Leach pp.452-469 transcribes The Incorporation, Statutes and Injunctions of the Cathedral Church of Canterbury in the original Latin along with a translation that is quoted here. Back to Text

- Note 12: Leach p.457. Back to Text

- Note 13: As well as those completing their 4-5 years of education, a vacancy might also arise if "any of the boys is found to be of remarkable slowness and stupidity or of a character to which learning is abhorrent, we will that after a long probation he shall be expelled by the Dean ... and another substituted, lest like a drone he should devour the bees' honey." - Leach p.457-9. Back to Text

- Note 14: Leach p.465. Back to Text

- Note 15: Edwards p.57-8. The former Prior's guesthouse was next to the old kitchen and named Meister Omer's house after a legal official to the Archbishop who used it in the thirteenth century. It was located at the west corner of the Green Court, with Mint Yard at the north corner. The building is labelled "Guests' Lodging" in the afore-referenced map of The Medieval Priory Church of Christ Church produced by the Canterbury Archeological Trust. The Cardinal was a guest of prebendary John Bungay, who resided in 'The Homers' at the east end of the Cathedral. Back to Text

- Note 16: , The Cardinal de Châtillon in England 1568-71 (1889) p.250, recorded in the Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London Vol. 3 (London, 1892) pp.172–285. Available at the Internet Archive. Back to Text

- Note 17: The date of the Cardinal's death is cited as 24 March by Atkinson and Edwards. Wikipedia states 21 March. The comtemporary and later reports of the Cardinal's death that Atkinson quotes pp.255-8 give varying dates. Back to Text

- Note 18: The full report of the Commission of Inquiry by Roger Manwood and Thomas Leighton addressed to the Earl of Leicester and Lord Burghley dated 30 March 1571, is reproduced by Atkinson pp.252-5 (see Internet Archive). A Latin epitaph written by "C.M." on the death of Sir Roger Manwood (1525-92) is generally attributed to Christopher Marlowe (with the caveat of J.P. Collier's involvement). Manwood, who lived at Hackington near Canterbury, was knighted and became Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1578. He was one of the judges in the trial of Marlowe and Thomas Watson in 1589 after the death of William Bradley in a duel with the accused. Marlowe was acquitted, and Watson was adjudged to have killed Bradley in self-defence. Back to Text

- Note 19: Atkinson pp.255-8 cites various references to the Cardinal being poisoned, and the later confession of his servant. From these and analysis of the Commission report, Atkinson's opinion was that Coligny was indeed poisoned. Back to Text

- Note 20: [Bakeless-Man] p.41 and Edwards (p.87) both specify that the scholarship was awarded to 'Christopher Marley' on 14 January 1579 although neither cite a source. [Urry-Canterbury] (p.42) says that the first payment on Lady Day 1579 means that Marlowe "became a scholar at the King’s School ... at Christmas in 1578". Bakeless also says that Marlowe filled a scholarship vacancy that arose on that date, and in The World of Christopher Marlowe (Faber & Faber, 2004) states specifically that the vacancy arose because "John Elmley lost his scholarship after the autumn term of 1578", citing Urry. But Urry (p.103) says only that the "this name [John Elmley] appears under Christmas 1578 only". The establishment was generally referred to as the Queen's School during the reign of Elizabeth I, hence Queen’s Scholarship. Back to Text

- Note 21: Canterbury Cathedral Archives, CAC (Chapter Archives, Canterbury), Miscellaneous Accounts 40. [Urry-Canterbury] pp.43-44 states that the annual accounts each running from Michaelmas (29 September) that detail payments to scholars are only extant for 1578-79 and 1580-1, the latter showing further payments of £1 to Marlowe at midsummer and Michaelmas 1580. Back to Text

- Note 22: Leach p.469. Back to Text

- Note 23: Edwards p.87. Back to Text

- Note 24: The curriculum described here is prescribed in the 1541 King’s School Statutes transcribed in Leach pp.467-9. Back to Text

- Note 25: [Urry-Canterbury] p.44. Back to Text

- Note 26: Etched by William Harvey from a drawing by F.W.L Stockdale after a sketch by William Woolnoth. Credit: W. Harvey, View of Canterbury showing the Green Court Gate. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Back to Text

- Note 27: [Urry-Canterbury] pp.49-52 and Appendix I pp.99-107. Back to Text

- Note 28: & , Schola Regia Cantauriensis: A History of Canterbury School commonly called the King's School (London, 1908), accounts leaf image from plate facing p.90. The boys' first names are Latinised. Back to Text

- Note 29: , Dr Simon Forman - A Most Notorious Physician (Chatto & Windus, 2001) p.4. Back to Text

- Note 30: , A Pleasant Comedie, called Summers Last Will and Testament (London, 1600) - see text at Internet Archive in [Nashe-McKerrow] Vol III p.280. Back to Text

- Note 31: , The Scholemaster (London, 1570), A Preface to the Reader. Back to Text

- Note 32: Ibid. Ascham, The first booke for the youth. Back to Text