Marlowe's Education

An Elizabethan Education

Whilst he may have braved Fortune's wheel by being born during a severe outbreak of the plague in Canterbury, Christopher Marlowe was far luckier in terms of time, place and of course gender for his educational opportunities. The early decades of Elizabeth's reign enjoyed what has been termed an "educational revolution",1 and whilst this was a long way short of providing free or affordable education for all,2 there was certainly an increase in both the demand and availability of schools for the sons of those on middling and even lower incomes. Educational institutions had long been closely associated with the country's Cathedrals to develop the next generation of clergy, and Marlowe may have also benefitted from the intake criteria of the Canterbury grammar school when it was re-founded in the reign of Henry VIII.

These improvements came as professional educators endeavoured to establish effective curricula at all levels of education that would meet the employment needs of tradesmen, craftsmen, as well as the higher calls of the church, the inns of court and other professions. Quite a number of teachers published works during Elizabeth's reign detailing and promoting a range of teaching practices.3

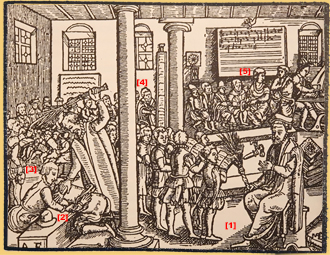

An elementary education in reading, writing and religious instruction was most widely available via 'petty schools' for children, ideally between the ages of about four or five and eight years old (although it was not unusual for older boys to be taught these basics as and when work and finance permitted).4 Both boys and girls attended petty schools, but subsequent education was almost exclusively for boys. Those with the aptitude, parental ambition and financial backing could advance to a grammar school where the curriculum taught them English and Latin grammar, Latin translation, classic texts, and the skills of oratory. A grammar school such as the King's School in Canterbury would take the boys through five or six classes, from the age of perhaps nine to fifteen or sixteen. Those aiming for university would need to stay the course, and the grammar school curriculum in the latter year or two was especially aimed at readying such students for university.

We know that Marlowe started at Cambridge University in December 1580 aged sixteen, and prior to that had been the recipient of some scholarship funding at the King's School in Canterbury from the start of 1579 (aged fourteen). To reach that stage, we might assume that he undertook both the elementary and full grammar school education. If he had followed the recommended school ages, Christopher might have attended some form of petty school between, say, 1568 and 1572 (aged four to eight) and then begun a grammar education some time in or after 1573 (aged nine).

Even if he had qualified, there were still often implicit costs in attending a 'free school'. The Marlowe family finances, and maybe even the need to help his father in the family shoemaker business, could have restricted a full-time education during Christopher's youth. It is possible also that an exceptional aptitude may have enabled him to move faster through the curriculum when he was able to attend. We know that John Marlowe took out loans from at least as early as 1570, but it is perhaps fanciful to imagine the money was borrowed to pay for Christopher's education.

On the other hand, John was able to take on a series of apprentices from 1567 onwards, perhaps lessening the need for young Christopher to contribute his labour to the family business. When the King's School headmaster John Gresshop died early in 1580, John Marlowe received money from his estate that was owed for the provision of lodging and footwear to two other pupils at the school, and it could be that such a contribution may have helped Christopher earn a place at the school and/or a scholarship. It should also be noted that Christopher was the only son during this period and thus likely the primary beneficiary of any family funds available for school fees. His only other surviving brother, Thomas, was not born until 1576, and thus only four years old when Christopher left for Cambridge on a scholarship in 1580.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: , The Birth of the Elizabethan Age – England in the 1560s (Blackwell Publishers, 1993) p.170: "One indication of the concern of adults for better education is the explosion of school foundations in the mid-century, leading to an ‘educational revolution’ between about 1560 and 1580. In the 1560s 42 new school foundations were added to 47 founded in the 1550s. Literacy rates improved sharply for people who were children early in Elizabeth’s reign. University enrolments jumped too. Cambridge matriculated about 160 students a year in the 1550s; by the 1570s the number had vaulted to 340 a year." Back to Text

- Note 2: , Literacy and the Social Order – Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge UP, 1980) p.19: "The eighty years before the English civil war may indeed have been a period of 'educational revolution' but for the majority of English children it was a revolution which passed them by." Back to Text

- Note 3: A number of contemporary publications covering different strata of education may reflect to a greater or lesser degree Marlowe's school experience. Most well-known perhaps is Roger Ascham (c.1515-1568), The Scholemaster (London, 1570), and whilst this was "specially prepared for the private brynging up of youth in gentlemen and noblemens houses", it is notable that the King's School headmaster John Gresshop owned a copy in 1580 when Marlowe was a pupil. Educator John Hart (d.1574) devised and promoted a radical phonetic approach to spelling in his reading primer, A Methode or Comfortable Beginning for All Unlearned, whereby they may bee taught to read English, in a very short time with pleasure (London, 1570). in The Petie Schole (London, 1576, 1587) details techniques for the teaching of reading, writing and numeracy to those starting their education (although in the extant edition published in 1587, Clement's introduction "To the courteous reader" is dated "21 of July 1576" and it appears from the title page that the sections on writing in the Secretary and Romaine hands, numeracy and "casting accomptes" were new in the 1587 edition). Richard Mulcaster (c.1531-1611) was headmaster of the Merchant Taylor’s grammar school in London from 1560-86, and in that time published two verbose treatises: Positions ... for the Training Up of Children (London, 1581), and The First Parte of the Elementarie (London, 1582). William Kempe (d.1601) was a Plymouth grammar school teacher and a Ramist (humanist) who discusses education for all classes in his The Education of Children in Learning (London, 1588). Edmund Coote, a former Headmaster of the Bury St Edmunds grammar school, published a popular teaching guide aimed at those without access to schools so that they might teach themselves: The English Schoole-Maister: Teaching all his schollers, the order of distinct reading, and true writing our English tongue (London, 1596). John Brinsley (bap. 1566 d. >= 1624), a schoolmaster in Leicestershire, published his Ludus Literarius or The Grammar Schoole (London, 1612), an approach to teaching based on his grammar school experience. Back to Text

- Note 4: Francis Clement [1576] recommended that a student could begin to learn the rudiments of spelling "though he be but foure years of age" [A4r] whilst lamenting "how fewe be there vnder the age of seauen or eight years, that are towardly abled, and praysablie furnished for reading" [A2v]. William Kempe [1588] would have a child begin his education when he was "about five years old", and have his pupils writing as well as reading by the age of seven. John Brinsley [1612] likewise recommended "that the child, if he be of any ordinary towardness and capacity, should begin at five years old". The Office of Christian Parents shewing how children are to be gouerned throughout all ages and times of their life [Cambridge, 1616] advised the "poorer sort" of parents that "once their child entreth into the eighth year of his age they should assuredly provide, if it be possible, that they may be furnished with the knowledge of reading and writing," whilst other children might be "perfect to read and write their own vulgar tongue" by the age of seven. Back to Text