Marlowe's Education

The Petty School

Regardless of social class, an elementary education was more widely available to many Elizabethan children via a 'petty school', which often taught both boys and girls. These varied greatly in both quality and cost, and ranged from dedicated, funded schools with professional teachers, through the teaching of young boys at grammar schools by ushers or older students, to an individual providing instruction perhaps in their own home (quite often women, leading to the term "dame schools").1 The majority of children from the middle and lower classes would learn to read and write at some form of school rather than being home-schooled by their parents, the fathers working and the mothers mostly illiterate.2

By the royal injunctions of 1559, teachers were supposed to be licensed3 under the authority of the diocese's bishop (here, then, Matthew Parker, the Archbishop of Canterbury), but this often resulted in religious orthodoxy taking priority over teaching ability. Schoolmasters were now examined along with the clergy at visitations. In addition, special inquiries could be made of schools and if the religious outlook of a master was called into question, any stipend from the crown could be withheld.4 The 'educational revolution' during the early decades of Elizabeth's reign can be evidenced in an increasing number of licensed teachers, particularly in London.5 Inevitably, others saw an opportunity for income by teaching a few petties without the need to obtain a license. Thomas Nashe remarked on "such as paste vp their papers on euery post, for arithmetique and writing-schooles".6

School fees varied. Some charged fees whilst others, particularly those founded by charitable endowments, were nominally free for some or all pupils. But even the latter might incur indirect costs, from the need for a student to supply his own learning materials to contributions to the upkeep of school and teacher(s).

After his apprenticeship had been terminated and he found himself unable to finance his own education, the twenty-year-old future astrologist Simon Forman managed to make ends meet by obtaining a teacher's post at the free school run by the St Giles Hospital in Wilton, Wiltshire. He claims he was paid 40 shillings for a half year (around 1s 6d per week) and taught 30 boys whose parents provided him with much of his food.7 Nashe, although perhaps more to make a comic point, put a teacher's wages much lower. Will Summer recalled how much he hated school, observing "Syntaxis and Prosodia, you are tormenters of wit, & good for nothing but to get a schoole-master two pence a weeke".8

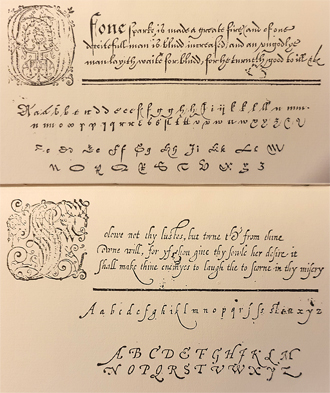

Petty Schools aimed to teach children to read and then to write, whilst also instilling the basics of the Elizabethan religious settlement from an early age. Initially children would learn to read orally from memory with the help of a hornbook showing "the foure and twenty letters, and the table of the syllables. These the scholler shall learne perfectly, namely, to knowe the letters by their figures, to sound them aright by their proper names, and to joyne them together, the vowels with the vowels in diphthongs & the consonants with the vowels in syllables".9 The hornbook was a common teaching aid, a wooden paddle that could be held by the child, and to which was pasted a lesson sheet protected by a thin transparent layer of horn from which the name derives. On the vellum or paper sheet was typically printed the alphabet in both upper and lower cases,10 a table containing some examples of consonant and vowel letter pair combinations (syllabless) to be sounded out, along with the Lord's Prayer.

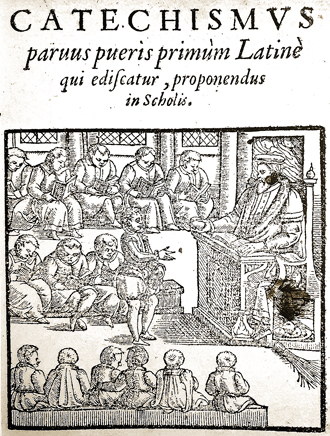

A similar approach of oral learned responses was adopted via catechisms to inculcate the essentials of the protestant religion in young minds, whilst also providing an opportunity to practise reading. Children would memorise answers to a series of religious questions as part of their confirmation, along with the Lord's Prayer printed on their hornbook and the ten commandments.11 The Book of Common Prayer printed during the first year of Elizabeth's reign (1559)12 included a relatively short catechism. Alexander Nowell, Dean of St. Pauls, produced a much-extended catechism in Latin in 1563 (Catechismus Puerorum) with more emphasis on the Calvinist doctrine. It was not adopted immediately, but after Archbishop Parker approved the printing of the original Latin version in 1570, an English translation by Thomas Norton was published the same year.13 The use of Nowell's Catechism was mandated in schools from 1571 onwards, providing both "a useful reservoir of spelling examples as well as a thorough review of the Christian religion".14

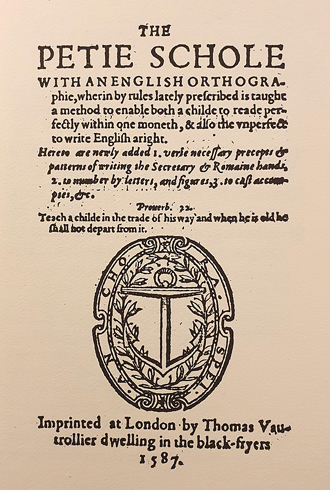

Francis Clement wrote the first edition of The Petie Schole in 1576, prescribing a rule-based approach to the teaching of reading and writing that may well have been familiar to Christopher Marlowe starting his education only a few years earlier. Teachers should "let the childe learne the vowels perfectly without the booke, so that he can readily rehearse them in this manner," then gradually build up the ability to recognise and pronounce consonants, diphthongs, syllables and thus the pronunciation of full words via a series of rules, examples and common mistakes. This formed a good basis for subsequently learning to write: "let him deuide [any word] into syllab[l]es. That done, he shall very easily perceiue what to write." Clement also provides guidance on the use of punctuation: "pointing" (full stops), "underpauses" (commas), "parenthesis" ("a payre of crooked lines"), "interrogation" (question marks) and "admiration" (exclamation marks).15

The textbook also includes a lengthy exhortation "to the petie scholer" as to the benefits and virtues of study and learning, with some examples from classical history. "So it is more certainly true," asserts Clement, "that this singular and precious bookeloue wil spedely [speedily] make thee a learned scholler."16 But perhaps mindful of the schoolboy mentality, he is quick to qualify his recommendation. "Bookeloue I say, but I meane not louebookes, which as they be the enemies of virtue, nources [nurses] of vice, furtherers of ignorance, and hinderers of all good learnyng: so doe they expresly represent the ougly shape and disguised image of that beastly, brutishe and furious loue, termed by Plato … a beastlike monstre with many heades".17

Clement was not a fan of the dramatic arts either. "I have yet further to warne thee of another monstre horrible to beholde, I meane common playes which do no lesse, yea rather more metamorphize, transfigure, deforme, peruert and alter the harts of their haunters." He cursed the "vile Theater", which "al[l] the honest abhorre" and pleaded to "now ceese adulterous playes".18 One might imagine a young Marlowe somewhat intrigued by mention of "lewd louebookes and Paganish playes" should his teacher have shared these admonitions with the class. Perhaps it was Clement who inspired the future 'plaiemaker' and translator of Ovid's Amores!

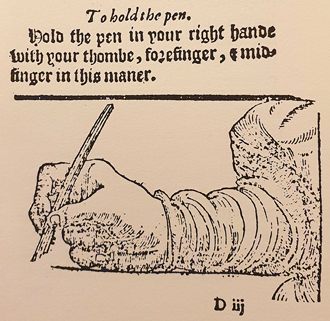

We get an insight into the equipment a young scholar would need. "The writer must prouide him these seuen: paper, incke, pen, penknife, ruler, deske, and dustbox, of these the three first most necessarie, the foure latter very requisite". A recipe for ink is given, made from "water, gumme Arabick, galles, and copras". Once mixed it should "stand couered in the warme sunne, and so will it the sooner proue goode incke. Refresh your incke with wine, or vinegar, when it wareth thicke".19 Advice is given on the best quills ("the third and fourth of ye wing of goose, or rauen"), instructions on how to make the pen ("Pare not off the barke and ouer parte of your pennes stalke, rather cut the fether away: for the stronger stalked it is in hand, the better will it deliuer the letters")20 along with detailed guidance and a diagram instructing the 'petie scholer' how to hold the pen.

It was noted when looking at contemporary Canterbury, that Archbishop Matthew Parker had shown an interest in the dilapidated Eastbridge Hospital and had reclaimed it in 1569 (when Marlowe was but five years of age), returning it to its charitable function distributing alms and maintaining twelve beds for the poor and providing food at the rate of 4d a day. The ordinances stated that part of the income thus received should be used to fund a free-school in the Hospital "for boys, not exceeding twenty, who were to be taught to read, to sing, and to write fairly: and especially the skills of singing and writing: and they were to have paper, pens, and ink, and other convenient books, provided them at the charge of the house. And no boy to stay at this school above four years, to make room for others. And three days in the week they were to sing aloud the Litany, or other short prayers. And the Master of the hospital was himself to be the teacher," he being provided with accommodation and "to receive yearly from the fruits of the lands and possessions of the hospital £6 13s 4d" as well as "12 cartloads of wood".21

Did Christopher Marlowe receive his elementary education at this newly opened free-school in the Eastbridge Hospital, a five-minute walk from his home along St. George's Street? There are of course no extant records, and it is unclear what selection criteria if any were applied for admitting boys, and whether John Marlowe's middling income as a shoemaker would have qualified or excluded Christopher. The school statutes suggest the school took in children aged 8 and upwards,22 and Marlowe turned eight in February 1572, which would have been a much later start to an elementary education than recommended by the educators of the day (see Schooling Note 4). That this was genuinely a free school which also provided the students with writing materials and books would doubtless have made it very attractive to John, as to other parents. Perhaps the fact that Christopher was later the beneficiary of one of two Parker scholarships to Cambridge University funded from the same source may provide a circumstantial link.

There were, though, other options available locally as the Elizabethan 'educational revolution' gathered pace in the later 1560's. Christopher may have attended a petty school run by the King's grammar school where ushers and older students would have taught elementary reading and writing to young boys. A petty school had also been recorded at a shop called the 'Fyle' on the High Street close to the Court Hall (where plays were performed before the mayor).23 Schoolmasters are also recorded residing in the parish of St George's around this time.24 Wherever Christopher learned the basics of reading and writing, they provided the grounding for a stellar career with the pen.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: was somewhat scathing writing his introduction to The Petie Schole (London, 1576) [A3r]: "Children (as we see) almost euerie where are first taught either in private by men or women altogeather rude, and vtterly ignoraunt of the due composing and iust spelling of words: or else in common schools most commonlie by boyes, verie seeldome or neuer by anie of sufficient skill". Back to Text

- Note 2: , Literacy and the Social Order – Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England (Cambridge UP, 1980) pp.40-41, citing 90% of women unable to write their names. This figure may well have included Marlowe's mother Katherine. She signed her will with a mark, but then again so did her husband John, who we know could sign his name as a younger man. Back to Text

- Note 3: Iniunctions geuen by the Queenes Maiestie, anno Domini 1559, the fyrst yere of the raigne of our soueraigne lady Queene Elizabeth, Imprinted at London in Poules church yarde by Richard Iugge and Iohn Cawood: 40. "Item that no man shall take vpon hym to teache, but such as shalbe allowed by th[e] ordinarye, and founde mete, as well for his learnyng & dexteritie in teachyng, as for sober and honeste conuersation, and also for ryght vnderstanding of Gods true religion". Back to Text

- Note 4: , Education and Society in Tudor England (Cambridge UP, 1966) pp.311-2. An example from the diocese of York is cited, where in 1564 a total of 57 teachers were examined: 32 were admitted to teach and catechise, 13 schoolmasters were admitted to teach alone, six clergy and one schoolmaster were admitted to catechise only, and two clergy and three schoolmasters were rejected as insufficient teachers. Back to Text

- Note 5: , The expansion of literacy: Opportunities for the study of the three Rs in the London diocese of Elizabeth I in Guildhall Studies in London History (Vol IV No 2 1980), who cites 68 licences issued in London in the decade 1570-9 and 211 licenses 1580-9. Back to Text

- Note 6: , Pierce Penilesse his Supplication to the Divell (London, 1592) - see text at Internet Archive in [Nashe-McKerrow] Vol I p.194. Back to Text

- Note 7: , Dr Simon Forman – A Most Notorious Physician (Chatto & Windus London, 2001) p.13. Back to Text

- Note 8: , A Pleasant Comedie, called Summers Last Will and Testament (London, 1600) - see text at Internet Archive in [Nashe-McKerrow] Vol III p.280. Back to Text

- Note 9: , The Education of Children in Learning (London, 1588) F2r. Back to Text

- Note 10: Hornbook sheets were often inscribed with a cross before the alphabet, leading to them sometimes being referred to as the Christ Cross Row, or Criss-Cross Row. Back to Text

- Note 11: , The Birth of the Elizabethan Age – England in the 1560s (Blackwell, 1993) p.166. Back to Text

- Note 12: This publication was largely a very little altered reprint of the 1552 Book of Common Prayer, published during the reign of Edward VI. Back to Text

- Note 13: , A Catechism, or, First instruction and Learning of Christian Religion translated out of Latin into English by Thomas Norton, Clerk (London, 1570). See also 1846 reprint at Internet Archive. Abridged versions were soon produced (1572 onwards – see a transcription of the 1572 Catechism printed by John Day). Back to Text

- Note 14: Cressy, p21. Back to Text

- Note 15: , The Petie Schole (London, 1587) A6r-B6v. Back to Text

- Note 16: Ibid C2r. Back to Text

- Note 17: Ibid C2v. Back to Text

- Note 18: Ibid C4v. Back to Text

- Note 19: Ibid D2v. Back to Text

- Note 20: Ibid D3r. Back to Text

- Note 21: (1643-1737), , The Life and Acts of Matthew Parker: the first Archbishop of Canterbury, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1821) Vol I, pp.566-7. Back to Text

- Note 22: Ibid. translates from the 1569 Latin statutes of Eastbridge Hospital to be found in Vol III Appendix Number LVIII pp.169-176. The Latin statute contains the statement (pp.173-4) "In qua ipse libere et gratis docebit et instruet, seu doceri vel instrui faciet, de tempore in tempus pueros supra aetatem septem annorum, et infra aetatem octodecim annorum, ad legendum, cantandum, et pulchre scribend", which indicates the master "will freely and gratuitously teach and instruct, or cause to be taught or instructed, from time to time, children above the age of seven years, and below the age of eighteen years, to read, sing, and write beautifully". Back to Text

- Note 23: , Addenda to volume 12: Minutes of the Records and Accounts of the Chamber, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 12 (Canterbury, 1801), pp. 612-662 at British History Online [accessed 27 November 2022]. In the Chamber of Canterbury records for 1544 it is stated that "The common clerk is to have one shop, adjoining the Court-hall, called the Fyle; upon condition, that he shall there, or one for him, do the duty of his office, and instruct children". Back to Text

- Note 24: [Urry-Canterbury] p.42. Back to Text