Marlowe's Childhood

Childhood Canterbury

Towards the end of the first century AD, following the Roman invasion of England, the newcomers began to develop the settlement they had named Durovernum Cantiacorum, strategically located at a crossing point of the River Stour on Watling Street, which connected London to the Kent coastal ports. Buildings included a temple, a forum, public baths (in use before AD 130) and aptly for our subject, an elliptical theatre with tiered wooden seating (completed by AD90, on the site of modern day Castle Street).1 The theatre was completely rebuilt in the early third century as "a monumental classical theatre in conventional D-shape … [with] banked seating facing the stage and orchestra … and the size of surviving foundations indicate a building dominating the city then as the cathedral does now".2 At the end of the third century, a bank and high wall were built around the city with up to seven gates,3 a fortification that still protected the city in Marlowe's time, and which indeed still largely defines the city's geography today.

Two centuries after the Romans had left, Pope Gregory dispatched Augustine to England to convert the Anglo-Saxon King (and King of Kent) Æthelberht to Christianity. The missionary landed in 597 with a group of monks and no little trepidation, but had soon succeeded in converting the King as well as establishing the see at Canterbury and becoming Archbishop. The first cathedral was built, as well as a monastery outside the city walls, later renamed St Augustine's Abbey. The cathedral would be enlarged and rebuilt a number of times, notably by Lanfranc three years after a fire had destroyed the building in 1067. A century later on 29 December 1170, Thomas Beckett was slain in the cathedral's north-west transept by four knights of King Henry II. The subsequent veneration of the Archbishop turned the Cathedral into a shrine and Canterbury into a hugely popular place of pilgrimage (as Chaucer shows in his Canterbury Tales).

In response to this influx of pilgrims into the city, many of whom were poor or sick, a number of hospitals were built to meet the demand for accommodation. The hospice of St. Thomas the Martyr upon Eastbridge was founded by Edward FitzOdbold around 1190,4 early in the reign of the new King, Richard I. Consisting of an entrance hall, refectory, chapel and an undercroft that provided a dormitory for pilgrims, it was built on the King's bridge where the High Street crosses the River Stour, not too far from the Westgate. Whilst repairs, restoration and changes were made to the hospital over the centuries (including a new Chapel roof in the late 13th century), as well as changes to its regulation and funding, the old Hospital building opposite All Saints church would have been one that was familiar to Marlowe, and remains in place today as the Eastbridge Hospital still providing charitable accommodation as an Almshouse.

Between 1536 and 1538, Canterbury's priory, nunnery and friaries were all closed as part of the dissolution, with St Augustine's Abbey being dissolved on 30 July 1538 and largely demolished in stages to provide building materials for castles and defences elsewhere. Becket's shrine was destroyed the same year, but a new foundation of Dean and Chapter was established in 1541, and of course Canterbury retained an Archbishop, albeit now Anglican.

Even with the destruction of the shrine to St Thomas the Martyr in Canterbury Cathedral, one religious house that survived the dissolution was the Eastbridge Hospital. The returns to Henry VIII's commissioners reported that the chapel, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, was a parish church ministering "to the poor people resorting thither", whilst the hospital had revenues of over £43 and a clear income of over £23 in 1535. Despite this, the hospital survived, and in 1557 was still "bound to receive way faring and hurt men, and to have eight beds for men, and four for women; to remain for a night, and more if they were not able to depart".5

As Elizabeth I set about re-establishing England as a protestant nation, she appointed Matthew Parker as her first Archbishop of Canterbury in 1559, a position he held until his death in 1575. The Archbishop's Palace in the Cathedral precinct had been badly damaged by fire in 1543, and remained in a dilapidated state. Although Parker's main residence was Lambeth Palace in London, he spent "upwards of 1400l" in his first two years as Archbishop rebuilding the Palace and Great Hall.6

Parker also took an interest in the Eastbridge Hospital. At the start of Queen Elizabeth's reign, the accommodation had been converted to private tenements, but on 20 May 1569 the Archbishop reclaimed the hospital and returned it to its charitable function by issuing new ordinances. It would once again provide "relief of wandering and wayfaring brethren, and poor, in bread and drink, after the rate of 4d. a day, and one night's lodging for twelve persons". It was stipulated that the Master of the Hospital (Parker himself) should retain the profits.

However, the ordinances also stated that the money thus raised would be "bestowed on certain poor inhabiting within the city of Canterbury", as well as paying yearly "towards the keeping of a freeschool, for a certain number of poor children of the said city, to be taught to write and read freely within the hospital". There are of course no records indicating whether the young Christopher Marlowe may have attended this school, but he certainly did subsequently benefit from another use of the revenues from the Eastbridge Hospital set up by Parker to pay for scholarships to Benet's (Corpus Christi) College at the University of Cambridge for two Canterbury scholars. A review in 1576 after Parker's death again found the hospital stood "ruinated" and that the accommodation was again being let out as private tenements. This time it fell to the new Archbishop John Whitgift to once again restore the accommodation for the poor, a school for twenty poor children, and the two Cambridge scholarships.7

Archbishop Parker was able to host the Queen during her progress through Sussex and Kent in the late summer of 1573. Elizabeth arrived in Canterbury on 03 September, attending a Cathedral service. Four days later on her fortieth birthday, Archbishop Parker entertained Elizabeth in the hall of his refurbished Palace with a great celebratory feast. Some ordinary citizens of Canterbury were allowed into the Hall to see the Queen and the assembled dignitaries,8 and there is a good chance that the nine-year-old Christopher Marlowe caught a glimpse of the Queen here or during her progress through the city streets.

By the time of Marlowe's baptism, Canterbury remained an important but relatively small city, still dominated by the cathedral. A survey in 1563 recorded 700 households, whilst a similar exercise six years later extrapolates to approximately 900 households and a population of 2,341 people above adolescent age.9 By comparison the cities of York10 and Norwich11 each had a population three or four times that of Canterbury.

Through Marlowe's childhood, the population of Canterbury was boosted by increasing numbers of "strangers", protestant refugees fleeing from the religious wars and persecution in both France and the Spanish Netherlands. The first arrivals in 1561 settled in Sandwich, and two years later Archbishop Parker visiting that town noted "the French and Dutch", writing in a letter that "profitable and gentle strangers ought to be welcome and not to be grudged at".12 Large numbers of French-speaking protestant Walloons fled to England from the Low Countries in 1567-70, and the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre in Paris in 1572 (later the subject of a Marlowe play of course) caused many thousands of Huguenots to leave France. The strangers were allowed to worship at the church of St Alphege in 1575, close to the Archbishop's Palace, but a year later the city took in 100 families from the increasingly over-filled Sandwich,13 and a larger space was needed. They were granted use of the Western Crypt of the cathedral for worship and as a school, for which they paid rent.

Walloon and French Huguenot protestant refugees were first allowed to use the western crypt of Canterbury Cathedral for worship in 1576, and there is still a French chapel in the crypt today [2021] where a French service is held every Sunday.

The refugees were indeed welcomed, initially living in empty tenements around the Blackfriars area along the River Stour to the north of the city, often 3 or 4 families in each. Their number included many craftsmen skilled in weaving (initially wool, later silk), and looms were set up in their houses to produce cloth, with many locals employed as a result. The Walloon community made collections to distribute to their own poor, and also administered fines to those found to have committed misdemeanours, and all of this helped them avoid being "grudged at". By the early seventeenth century, it is estimated that 40% of Canterbury's population of 5,000 consisted of these settled refugees.14

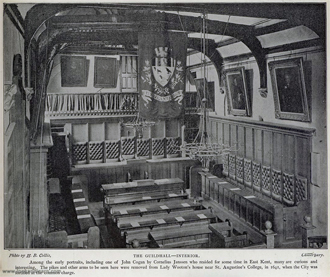

At this time, Canterbury was also a major stop on one of the established theatrical touring circuits15 and there were regular performances in the city whilst Marlowe was growing up. From the start of Elizabeth's reign until Marlowe left for Cambridge at the end of 1580, there are only three years in which the City Chamberlain's Accounts fail to record payments to visiting acting troupes.16 Regular performers paid "at Master mayers comandyment" include "my lord Robert d[u]dleys players", "my Lord of oxefordes players", "ye Qwenes maiesties playars", "my lord off h[u]nsdons players", "my lord of sussex players" and "my lord strayngys players". In December 1574, payment is recorded to "the lord of leycester his players for playeng before Master Mayer & his bretherne at the Courte halle".17 A number of performances are recorded in subsequent years at the same venue, which may have been the Guildhall on the High Street. It is likely that other performances occurred at inn yards and other public venues at this time which are not recorded by the official city accounts. Later, in the early 17th century, there are records of performances at The Chequers Inn on Mercery Lane, and The Red Lion Inn next to the Guildhall.18

The old inn called the Cheker (or Chequer) of Hope had been (re)built in 1392 by the Christchurch Priory at great cost to meet the accommodation needs of visiting pilgrims.20 It is mentioned by Chaucer in his "Tale of Beryn" that his story-telling pilgrims "They toke (t)h(e)ir in and lo(d)ged (t)hem at mydmorowe, I trowe, atte Cheker of the Hope, that many a man doth knowe". Marlowe would later be charged with assaulting the tailor William Corkyn nearby in September 1592. The inn closed circa 1825, and was damaged by fire in 1865, but part of the surviving building can still be seen on the corner of High Street and Mercery Lane.

There is no extant evidence of Marlowe partaking in theatrical performances whilst a student at the King's School (1578-80), but records before and after his time suggest plays were performed by the boys. In October 1562, funding of £3 6s 8d is authorised by the Cathedral authorities to pay schoolmaster Anthony Rushe "in settyng f(o)rthe of (tra)gedies Commedyes and interludes this next (Christ)mas".21 It is perhaps no coincidence that John Bale (1495-1563) was a Cathedral prebendary at this time, he having written mystery and miracle plays back in the reign of Henry VIII, as well as an early English historical drama Kynge Johan (1538).

In 1592, one Edwards and William Symcox were before the courts charged with luring away scholars from the King's School to join a travelling band of actors. The pair "inveigled the scolars ... to go abrode in the c(o)untrey to play playes contrary to lawe and good order". They compounded their offence when "afterwards, the said scolars beinge in pryson for theyr said contempt, ... the said edwardes and symcox came to them and there dyd an(i)mate the said children to playe in contempte of the commandement, ... and hanged owte a sho or a pott to beg wythall", offering the boys "as good recompence as they shuld haue by the scole yf they dyd gyve over or lose theyr place".22 The pair of miscreants confessed to their transgressions before a subsequent hearing, promised to mend their ways, and escaped with a caution. But we may perhaps infer that the schoolboys had some basic acting experience if they were in such high demand.

Such regular theatrical performances in the city may have inspired the locals in different ways. As well as Marlowe in this period, the small city of Canterbury also produced the noted playwright John Lyly (1553/4-1606), the son of the Registrar to Archbishop Parker who wrote his two Euphues and many other plays from 1578 onwards. Meanwhile, a contemporary Stephen Gosson (1554-1624) began by writing plays but is best remembered for his anti-theatrical Schoole of Abuse, containing a pleasant invective against Poets, Pipers, Plaiers, Jesters and such like Caterpillars of the Commonwealth (1579).23

Footnotes:

- Note 1: Marjorie Lyle, Canterbury – 2000 Years of History (Tempus Publishing, 2002) pp.32-35. Back to Text

- Note 2: Ibid pp.32-33. Back to Text

- Note 3: Ibid pp.43-46. Back to Text

- Note 4: Ibid p.84. Back to Text

- Note 5: Edward Hasted, Precincts Exempted from the City Liberty: The Hospital of King's Bridge, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 12 (Canterbury, 1801), pp. 115-135. British History Online [accessed 01 February 2022]. Back to Text

- Note 6: Edward Hasted, Canterbury: Archbishop's Palace and Precincts, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 11 (Canterbury, 1800), pp. 294-303. British History Online [accessed 10 July 2021]. Back to Text

- Note 7: Edward Hasted, Precincts Exempted from the City Liberty: The Hospital of King's Bridge, in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent: Volume 12 (Canterbury, 1801), pp. 115-135. British History Online [accessed 01 February 2022]. Back to Text

- Note 8: [Urry-Canterbury] p7. Back to Text

- Note 9: [Urry-Canterbury] p2. Urry estimates that "the population of Canterbury in the 1560s was probably somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000 persons". The Black Death had decimated the booming city's population from the mid-fourteenth century onwards. Lyle (p.86) estimates a population of 10,000 before the first serious outbreak in 1348, reduced by 70% by the early 1500s. Back to Text

- Note 10: Nadine Lewycky, The City of York in the Time of Henry VIII (The University of York: Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past, 2010) p.14: "Despite … shrinking from 12,000 to 8,000 people by the 1520s, the population of York recovered in the Elizabethan period, reaching levels of 11,500 by 1600." Back to Text

- Note 11: J.F. Pound, The Norwich Census of the Poor 1570, Norfolk Record Society 40 (1971), p.10. Pound estimates the population of Norwich in 1570 to be 10,625 people. Back to Text

- Note 12: John Strype, The Life and Acts of Matthew Parker (Clarendon Press, London, 1821) Vol I p.276. Back to Text

- Note 13: Lyle, p.107. Back to Text

- Note 14: Ibid. Back to Text

- Note 15: Scott McMillin & Sally-Beth MacLean, The Queen's Men and their Plays (Cambridge University Press, 1998) p.39. Their list of established tour circuits post-1550 includes one to "the south-east through Canterbury to the Cinque Ports and their coastal affiliates". Back to Text

- Note 16: Records of Early English Drama [REED], KENT: Diocese of Canterbury Vol 1, Alkham to Canterbury, Ed. James M. Gibson (British Library & University of Toronto Press, 2002) pp.180-212 referencing Canterbury Cathedral Archives (CCA) City Chamberlain's Accounts CC/FA 16 to 18. The three years without any such payments were 1567-8, 1571-2 and 1577-8. Back to Text

- Note 17: Ibid p.205 referencing City Chamberlain's Accounts CCA: CC/FA 17 f 291. Back to Text

- Note 18: Ibid p.75. Back to Text

- Note 19: Illustration from Canterbury, Mother-City of the Anglo-Saxon Race (Canterbury Chamber of Trade, 1904). Image licensed by Look & Learn History Picture Archive. Back to Text

- Note 20: Canterbury Historical and Archaeological Society website [accessed 16 July 2021]. See also the Dover-Kent Archives and Historic Canterbury websites. Back to Text

- Note 21: REED p.192 referencing Cathedral Chapter Act Book CCA DCc/CA 1 f28v, dated 27 October 1562. Back to Text

- Note 22: REED p.228 referencing Court of High Commission Act Book CCA: DCb/PRC 44/3 pp103-4 (16 March 1592). Back to Text

- Note 23: The Luminarium website has a textual transcription of Gosson's Schole of Abuse [accessed 01 February 2022] Back to Text