Marlowe's Childhood

John Marlowe's Career

Having been born in the village of Ospringe, close to Faversham, it seems likely that Marlowe's father came to Canterbury around the age of twenty,1 circa 1556 during the reign of Queen Mary. The first record of him in that city is when one Gerard Richardson, shoemaker, paid the sum of 2s 1d to the city authorities to enrol John Marlowe as his apprentice in the year 1559-60.

John became a freeman of Canterbury on 20 April 1564, two months after Christopher's birth:

ye xxth day of aprill in ye yere a fforeseid [1564] John Marlyn of Canterbury sho[e]maker was admitted & sworne to the liberties of ye cittie 2

This entitled him to trade independently in the city, including the license to display and sell his goods via a ground-floor window at his home if he chose to do so. An apprenticeship of just four years would be unusually short, and John Marlowe may already have begun learning the cobbler's trade before starting his apprenticeship with Richardson, either in Faversham or Canterbury.3

Within a year John had his own shoemaker's shop,4 likely in the same house in St George's parish where the family lived with their two young children Mary and Christopher. In 1567-8 John enrolled the first of at least five apprentices during his career. Richard Umberfell worked for Marlowe for around two years before he fell under a cloud and left abruptly, accused of having gotten Joan Hubbard of the same St George's parish pregnant.

Marlowe's workshop was never a dull place it would seem. Lactantius Presson was enrolled in April 1576 when Christopher was 12 years old, but left within 16 months after a fight with his master, John Marlowe "fined for drawing blood". In the summer before Christopher left for Cambridge, Elias Martin and William Hewes were enrolled as apprentices in July 1580. Both would go onto become freemen of Canterbury in the 1590s, although Hewes did not appear to bear his former master much gratitude, for he was convicted of assaulting John Marlowe before Christmas 1594 near the Buttermarket in Canterbury. Thomas and Edward Mychell were both apprentices to John after his son Christopher's death, the latter served with a bastardy bond in 1598 after Marlowe's servant Alice Alcocke bore a child.5

In between the punch-ups and pregnancies, John Marlowe was held in sufficient regard by his fellow tradesmen to hold various official positions in the Company of Shoemakers. In 1570, his name is second on a list of shoemakers signing a formal petition to the Justices of the Peace.6 If these represent the seven officers of the Company ranked, then John Marlowe would have been one of two wardens, second only to the Master. He was appointed a Searcher (inspector of leather) in 1581-2, and elected as both warden and treasurer of the Shoemakers' Company in 1589. At the end of his year in office, however, a shortfall of over 40s was found. The company eventually entered a case against Marlowe on 27 January 1592,7 and despite protesting that he had already paid the missing sum, the verdict went against him in April.8 He somehow managed to pay off this sizable debt by the end of the year, and his reputation remained sufficiently intact for him to be listed as a Company Assistant in 1601-02, one of four such officers ranked below Master and Warden.

Despite the missing Shoemakers' funds, and the non-payment of rent pursued by his landlords in 1584 and 1594, it is perhaps difficult to judge John Marlowe's business acumen at the distance of more than four centuries. Like many of his contempories he took out loans regularly. He borrowed £2 from the Wilde Charity in 1570 (a debt still outstanding in 1573), £5 from the Streater legacy in 1586 and perhaps also loaned sums from Alderman John Rose, since he still owed 10s on Rose's death in 1591.10 We may though surmise that it was perhaps fortunate that Christopher was able to gain a non-fee-paying place at King's School late in his education, and soon after become the recipient of a funded scholarship to Cambridge University.

However he may have conducted his business affairs, John Marlowe still fulfilled his civic and community responsibilities. In 1588, with the country under threat from the Spanish Armada, he enlisted to serve at the age of 52 in a "Selected & Enrolled Band" comprising 200 local men. He is recorded as possessing various weapons in his house, including bow, sword, dagger and halberd. The Canterbury band saw no direct action, but did capture a "trayterous spye" named Field who was subsequently hanged at Tilbury.11

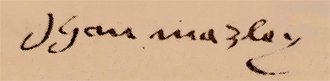

That John Marlowe appears as both plaintiff and defendant in at least 18 cases in the Canterbury borough pleas book during Christopher's life hints at a vigorous character even in such a litigious age. He had basic literacy, able to sign his own name and write a few words. His signature regularly confirms him as witness or bondsman on legal documents, most notably on the will of Katherine Benchkin.12 He regularly stood as a juryman, acted as Sidesman at different churches, and was Churchwarden in the parish of St. Mary Breadman between 1591 and 1594 where the family then resided.13 He was simultaneously constable of Westgate in 1591-2, and may have been somewhat embarrassed at having to find surety for his son Christopher, accused by one William Corkine of attacking him with "staff and dagger" in Mercery Lane in Canterbury on 15 September 1592.

In later life, John Marlowe may well have retired as a shoemaker. In his late sixties, he was licensed in 1604 "to kepe comon victualing in his nowe dwelling howse".14 It may also be telling that no tools of the shoemaker's craft were listed in the inventory of his possessions just after he died.

Footnotes:

- Note 1: [Urry-Canterbury] p13, based on his more likely year of birth as 1536 – see Parents - footnote 3. Back to Text

- Note 2: Canterbury Cathedral Archive & Library, Accounts 1558-68. Back to Text

- Note 3: [Urry-Canterbury] p13. Back to Text

- Note 4: [Urry-Canterbury] p21 and pp.29-30; [Kuriyama] pp.12-13. Evidence given in a case brought against Marlowe's friend Laurence Applegate who had a tailor's shop on the High Street, and who was accused of defaming Goodwife Chapman's married daughter Godelif Hurte. He claimied to have "occupied" her on four occasions, and some of these "bawdy remarks" were made in Marlowe's shop. Back to Text

- Note 5: [Urry-Canterbury] on John Marlowe’s apprentices pp.23-25. Back to Text

- Note 6: [Urry-Canterbury] p23. Back to Text

- Note 7: [Urry-Canterbury] By coincidence, his son Christopher was most likely on that very day sailing on a ship back from Flushing to England, extradited along with his nemesis Richard Baines on a charge of 'coining' (counterfeiting) a Dutch shilling. Sir Robert Sidney's covering note to Lord Burghley is dated the previous day. Back to Text

- Note 8: [Urry-Canterbury] p26. Back to Text

- Note 9: Julian Bowsher & Pat Millar, The Rose and the Globe - Playhouses of Shakespeare's Bankside, Southwark - Excavations 1988-90 (Museum of London Archaeology, 2009) - pp.196-7. Back to Text

- Note 10: [Urry-Canterbury] p26. Back to Text

- Note 11: [Urry-Canterbury] pp.30-31. Back to Text

- Note 12: Dated 19 August 1585, the will also contains the only extant signature of his son Christopher, then aged 21. Back to Text

- Note 13: John Marlowe was also recorded as "clarke of St Maries" at his death in St. George's burial register entry for him in 1605. Back to Text

- Note 14: [Urry-Canterbury] p38. Back to Text